Before you raise money as a cash-strapped fledgling startup, it can feel like every problem you are experiencing would go away if you just had some money in the bank. At TechCrunch, it often seems as if every other startup story is about yet another fun company raising satchels full of venture capital.

Millions — billions — of dollars are flowing toward upstart tech companies of all stripes, and as the de-facto news hub for the startup ecosystem, we are as guilty as anyone of being a little bit on the “cult of capital” side of things. One truth is that successfully raising capital from a VC firm is a huge milestone in the life of a startup. Another truth is that VC isn’t right for all companies. In fact, there are significant downsides to raising money from VCs. In this piece, I’m taking a look at both sides of the coin.

I have two day jobs. One is as a pitch coach for startups, and the other is as a reporter here at TechCrunch, which includes writing our fantastically popular Pitch Deck Teardown series. Before these two day jobs, I was the director of Portfolio at hardware-focused VC fund Bolt. As you might expect, that means I talk to a lot of early-stage companies, and I’ve seen more pitch decks than any human should.

A lot of the pitch decks I see, however, make me wonder if the founders have really thought through what they are doing. Yes, it’s sexy to have a boatload of cash, but the money comes with a catch, and once you’re on the VC-fueled treadmill, you can’t easily step back off. The corollary of that is that I suspect a lot of founders don’t really know how venture capital works. That’s a problem for a number of reasons. As a startup founder, you’d never dream of selling a product to a customer you don’t truly understand. Not understanding why your VC partner might be interested to invest in you is dangerous.

So let’s take a look at how it all hangs together!

Where VCs get their money

To really understand what’s going on when you raise venture capital, you’re going to need to understand what drives the VCs themselves. In a nutshell, venture capital is a high-risk asset class that capital managers can choose to invest in.

These fund managers, when they invest in venture capital funds, are known as limited partners, or LPs. They sit atop giant piles of cash from — for example — pension funds, university endowments or the deep coffers of a corporation. Their job is to ensure that the giant pile of cash grows. At the lowest end, it needs to grow in line with inflation — if it doesn’t, inflation means that the buying power of that capital pool is shrinking. That means a few things: The organization that owns the cash is losing money, and the fund manager is probably going to get sacked.

So, the lowest end of the range is “increase the size of the pile by 9% per year” to keep up with the current inflation rate in the U.S. Typically, fund managers beat inflation by investing in relatively lower-risk asset classes, a strategy that works better in lower-inflation environments. Some of this low-risk investing may go to banks, some of it will go to bonds, while a portion will go into index and tracker funds that keep pace with the stock market. A relatively small slice of the pie will be earmarked for “high-risk investments.” These are investments that the fund can “afford” to lose, but the hope is that the high-risk/high-reward approach means that this slice doubles, triples or beyond.

Asset managers for these huge funds can choose to invest in any number of asset classes. Some might speculate on art, high-risk stock market investments, cryptocurrencies, high-risk real estate or even speculative research.

One of the asset classes they may choose to invest in is venture capital. The way that works is that an asset manager finds a venture capital firm they believe in and invests capital into a particular fund that the firm is compiling. VC firms tend to have an investment thesis for this reason: A particular fund might want exposure to biotech, or companies in the U.S. Southwest, or startups in developing markets, or only very late-stage companies. The investment thesis has an expected return range and a calculated risk ratio. If the VC firm invests at the earliest stages, for example, there’s a pretty decent chance that the company fails and it loses its investment — at the same time, if that deal succeeds, the venture firm could stand to see a huge exit with a terrific return. Investing at a much later stage could mean that there’s less risk (the company probably already has a product, a product-market fit and a pretty fair shot at success), but there’s also less of a chance that you will 10x your money.

Your investor has an investment thesis. Here’s why you should care

The reason fund managers invest in venture capital funds is that this gives them a portfolio. That means that their risk is spread out across a number of startups — instead of putting $100 million into one company that may succeed, venture capital is, in effect, spread-betting across a large number of startups, putting $5 million into 20 startups, for example. That means that even if 90% of the startups fail, the two that are left standing could well prove to be the next Facebook or Tesla. This can generate huge returns for VCs and their LPs alike.

Some venture firms only have one LP. In that case, the firm is usually either investing money from a corporate source (known as a corporate venture capital firm, or a CVC) or from a high-net-worth individual (usually known as a “family office”). You’ll come across both from time to time, but the vast majority of VC firms have multiple LPs. That means multiple investors and sources of money, and multiple sets of desires and expectations of how the VC firm performs.

What VCs do with the money

Now that you understand where VCs get their money, it’s important to understand how they work. In short, they are trying to deploy a fund into a set of startups that matches their hopes, dreams and ambitions. Ultimately, there are just two goals. The lowest possible goal is to return the fund (i.e., if an investor put in $10 million, they get $10 million worth of disbursements from exits and acquisitions).

But remember that “at least you got your money back” is a terrible outcome here; the LPs invested in a high-risk asset class. I’ve spoken to VCs who have the opinion of “I’d rather they run the startup into the ground and return nothing than get a 1.5x return on investment.” It’s hard to say how prevalent that opinion is, but it makes sense from the portfolio math point of view.

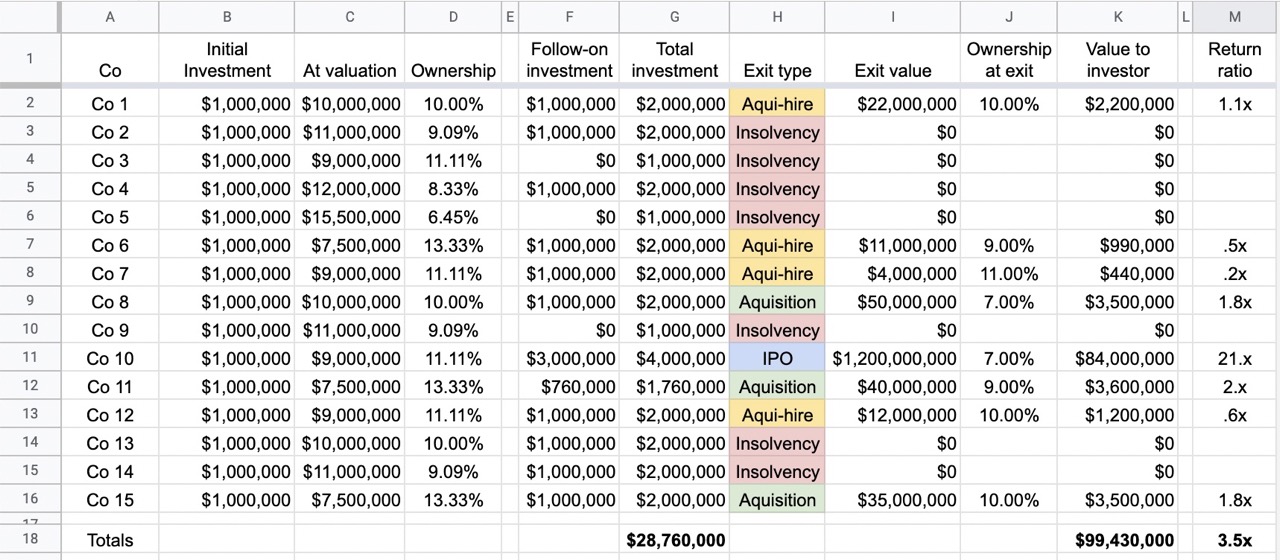

To explain how that works, take a look at this spreadsheet I threw together, which captures the portfolio of a made-up $30 million fund. It invested $1 million into 15 companies and kept an additional $15 million available for pro-rata rights and follow-on investments:

The “initial investment” portion of the spreadsheet should make sense to everyone. But what about those follow-on investments? To understand them, we need to discuss the concept of pro-rata rights. Pro-rata rights mean that when the investor made an initial investment, they included a clause that means that they can “top up” their investments to maintain the ownership in the company at the value of subsequent rounds. So if the fund owned 10% after the initial investment, and there’s another financing, they have the right to maintain their 10% ownership, if they can afford to invest along the new investor’s terms. Now, as the company raises more and more money, it’s unlikely that a small fund is able to maintain its ownership stake, so they’ll get diluted down along with the founders and other early-stage investors.

Part of the strategy of running a venture fund is deciding which companies to keep putting money into and which to give up on.

From the completely made-up example above, you can see that the portfolio of 15 investments resulted in one IPO, three decent acquisitions and four small acquisitions. For simplicity, I’m calling them “acqui-hires” here. Companies acquiring other companies for their team (acquisition-to-hire) is one scenario, but some companies just get sold in a fire sale for their intellectual property, for their customer lists, to kill off a competitor or any number of other reasons. I won’t go into them all here, but typically, these are relatively poor exits for the investors.

As you can see from the example above, even the pretty decent acquisitions were relatively small, and the only reason the fund made a substantive return, in this case, was Company No. 10. The venture firm invested $1 million initially for 11% ownership. It then poured an additional $3 million into the company — clearly, it participated in some follow-on rounds — and ended up with 7% ownership at an IPO valuing the company at $1.2 billion. That is what we call an “outsize return” in the business.

The important thing you need to understand from the above is that VC investing is a hits-driven business. A 2x or 3x return on investment isn’t really going to move the needle because the portfolio model of VC means that there are going to be a lot of misses, too. A 3x return sounds good, but in effect, it only makes up for two or three other investments that failed, leaving the VC firm at a net zero.

What the VCs are looking for is a “fund-returner” — if it’s a $30 million fund, an exit that is worth $30 million or more. Realistically, venture capital firms have costs as well (typically 2% of the fund), and the VCs only really start making money (the “carry” of the fund) when they have returned the invested funds to their investors — after costs are taken off. In other words, a $30 million fund doesn’t really start making money for the VCs unless it is able to return the $30 million plus 2% per year that the fund is running. For a 10-year fund, that means $6 million of management fees over 10 years. In addition, the firm will need to beat inflation to make any sense to its LPs.

The way the VC makes most of its money isn’t its 2% per year management fees (a common percentage), but the 20% “carry” that most funds get (the number can vary, but 20% is the benchmark figure). The way carry works is that once the LPs have their money back, the venture fund gets a 20% cut of any profits beyond that threshold.

So, in the hypothetical example above, the VC stands to make $6 million over 10 years from management fees and an additional $12.7 million of carry.

Imagine that this venture fund has five equal general partners and that nobody else has any carry in the fund. That means that each partner will get a $2.5 million payday after 10 years of work — or an average of $250,000 per year. That’s not pocket change, but there are less stressful ways of making $250,000 per year. (The management fees are also paid as wages and cover things like office rent, marketing spending, etc., but typically the general partners don’t pay themselves much out of the management fees.)

Can your company be a fund-returner?

Over 10 years, 5% average inflation and 2% of management fees mean that the opportunity cost to the LPs is almost $60 million on our invented $30 million fund. (Compound interest is the eighth wonder of the world, as someone far smarter than me once said). So for a 10-year investment period — the standard fund lifecycle — to make any sense at all, a VC firm needs to turn $30 million into at least $60 million.

By now, you’ve probably realized a couple of things — for one thing, VC investing is pretty damn stressful. The other: The benchmark against which your company is graded is very high. For a venture investment into your company to make sense, ask yourself this question: Could the investment the VC firm is about to make in your company potentially return its entire fund?

Or, put differently, if you are about to take a $1 million investment at a $10 million valuation, giving the investor 10% of your company, you would need to have a fighting chance at exiting your company at $600 million or more. And that is before the investor has exercised any of its pro-rata rights.

You sometimes hear, “Can this founder team take this company and turn it into a billion-dollar exit?” The phrase isn’t hyperbole. In a lot of situations, VC firms need a billion-dollar exit to return their fund. That doesn’t mean that anything less than a billion-dollar outcome is a failure, but this is where a lot of startup founders misunderstand how VC works. If there isn’t at least a tiny sliver of a chance that your company turns into a billion-dollar company, why should the VC place a bet on you?

A 3x or 4x return might be great for you, the founder, and perhaps for your early angel investors. For the VC industry, though, they’re looking for much higher potential than that. If everything goes perfectly to plan — your company gets everything right and sees a huge tailwind, where everything goes better than your wildest dreams — and you’re still not able to get the VCs to fund-returning-sized returns, you’re not in the right room. You’re selling something that doesn’t work within the VC model, which means you’re simply not a good investment.

I speak to a surprising number of founders who don’t understand the above, and who set themselves up for failure when they are on the fundraising path. You’ve got to think big, and the numbers in your financial projections have to back up that you have the weensiest mote of a chance at making everyone around the table a godawful amount of money. If you can’t do that, it’s back to the drawing board.

Comment