It’s data season, with groups like Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), CB Insights, PitchBook and Crunchbase News putting out data sets that we’re having fun exploring. This morning, we’re adding one more to our arsenal.

The Exchange spent some time this week diving into the SVB “State of the Market” report for the fourth quarter. As is common from the bank’s publications, it’s a dense riff of charts and notes, ranging from economic data and trade figures to venture capital statistics.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

While perusing the collected information, we found an interesting pattern: Venture capital investors are racing to pay more to buy smaller pieces of startups that are less profitable than before.

While that may sound somewhat rude, it isn’t. Instead, the capital crush that we’ve seen overtake startups around the world, the round preemption that has become common, the rising valuation marks that have become the entry price to hot startups’ cap tables and investments into growth have all come together to create a venture capital market unlike any that I can recall.

SVB gave The Exchange permission to share a few charts, so what follows is a graphical dig into the data, proving that I am not a brat for claiming that venture investors are getting a rawer deal than usual but merely sharing what the data indicates.

SVB gave The Exchange permission to share a few charts, so what follows is a graphical dig into the data, proving that I am not a brat for claiming that venture investors are getting a rawer deal than usual but merely sharing what the data indicates.

Less for more

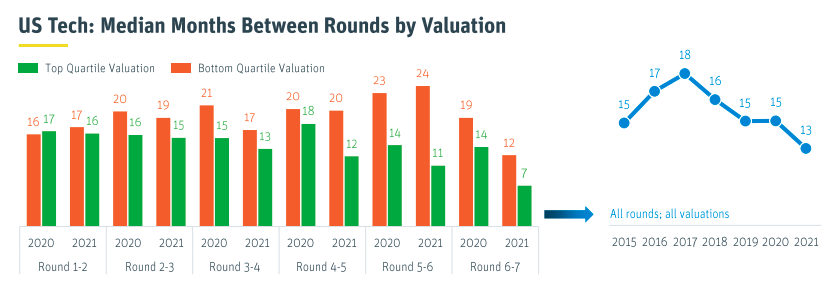

First, let’s examine how the time between funding rounds has fallen. SVB data shows a useful 2020 versus 2021 differential, with an aggregate chart tracking the same data over a longer time period on the right:

Image Credits: SVB

As you can see in both charts, venture capitalists are accelerating the pace at which they make successive investments into startups. This is what we meant by faster.

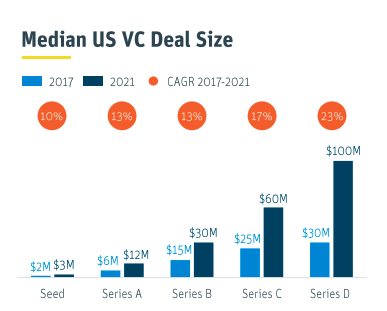

But putting more capital into startups more quickly isn’t cheap. Deals are getting bigger over time, and they are growing the fastest at the later stages of the market. As we can see in the following SVB graphic, the compounded growth rate of Series D rounds is higher than the growth rates posted by earlier rounds. Also note that there is an upward swing to round CAGR as we go up the startup maturity lifecycle:

Image Credits: SVB

That is what we meant when we said VCs are paying more. Another way to consider how they’re paying more is to look at the multiples, which SVB notes are also rising. For example, late-stage multiples for enterprise software firms rose 30% from 2020 to 2021. Consumer internet companies posted an even greater year-over-year gain.

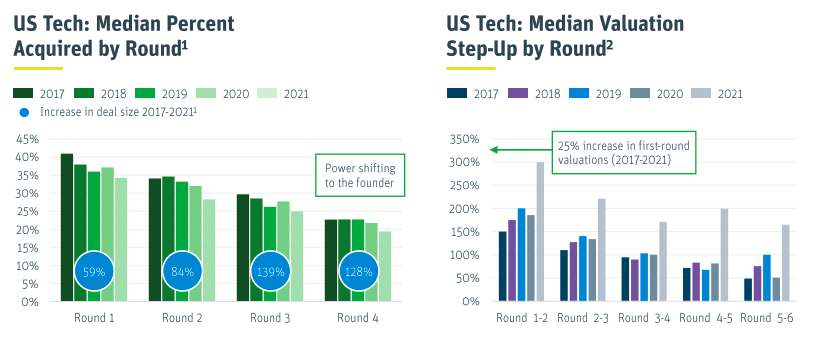

And what are venture investors getting for bigger rounds at higher multiples? Less ownership!

Image Credits: SVB

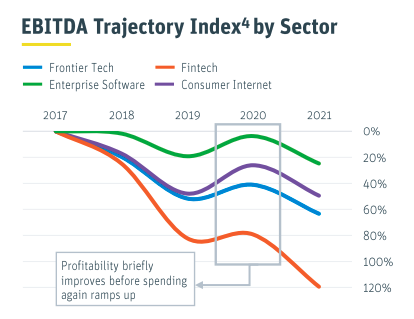

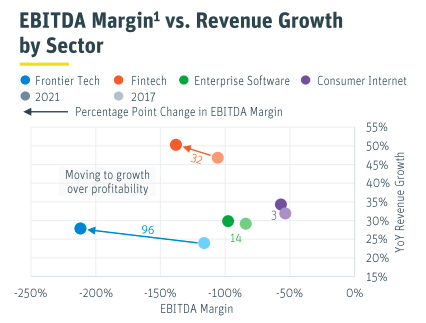

But don’t worry, the companies in question are also losing more money than before. Here’s what EBIDTA results look like for a few startup sectors over time:

Image Credits: SVB

Paying more and at shorter intervals for less of less profitable startups may sound like a raw deal. But there’s one thing that we haven’t touched on: growth.

Investors paying more for startup equity could make sense if startups are growing more quickly. If, for example, startups were growing 50% more rapidly as a group, then all the above would simply be the result of startups suddenly being worth more than before and the market adjusting to that fact.

But are they really growing more quickly? Yeah, but not by that much:

Image Credits: SVB

This chart is a little hard to read, so let me help. You want to see the dots go up and to the right. If they go up and to the left, it implies more rapid growth but at the cost of profitability. Every set of dots here is moving up and to the left, not the right.

So, the rising losses we saw before are tied to accelerating growth, just not as much for enterprise software and consumer internet companies as we would have anticipated. And the faster growing categories — frontier tech and fintech — are the two least profitable groups, implying that their growth is dearly bought.

All this is to say that the stuff we’ve been tracking in 2021, a year in which every round is seemingly preempted and there is no revenue multiple that VCs can explain away with future TAM calculations, really is changing what professional startup investors are getting for their dollar.

It’s a great time to be a founder.