Agriculture has a 10,000-year history, and it’s predominantly a history of technology. Developments from the plow and wheel to enclosures and the modern mechanical miracles of gas-powered tractors and sorters have consistently improved crop yields, allowing humanity to expand from tens of millions of people to a global population projected to top 10 billion this century.

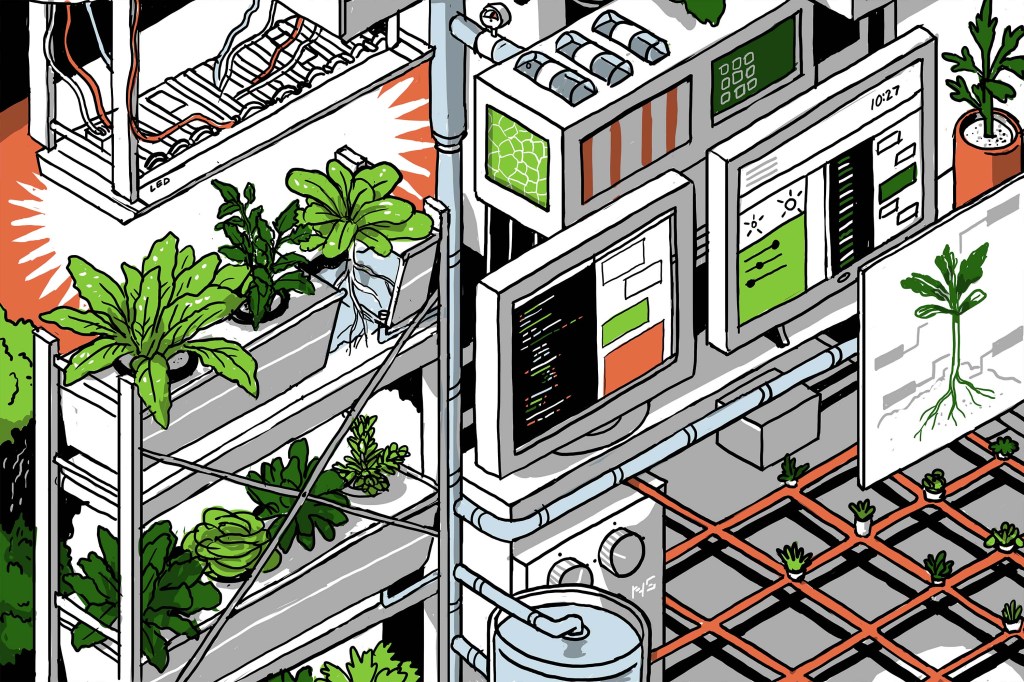

When it comes to the next stages of that long course of innovation, vertical farming would seem to have all the right properties. Precise controls backed by data analysis can calibrate food quality, leading to further improvements in yields while reducing raw inputs like water. That’s critical at a time when the world’s climate is increasingly at a breaking point.

For Bowery Farming, no technology is too small to optimize, and no data is too insignificant to track. Combined together, the startup hopes to orchestrate the future of farming — and build a competitive moat in the process. To ultimately create a company of value, it needs to not just build differentiated technology but also build a brand with consumers, which we’ll turn to in the final part of this TC-1.

In parts one and two, I covered the history of vertical farming, Bowery’s origins and how it develops produce. In this third part, I’ll look at the company’s core tech infrastructure, explore how developments of just one component, LEDs, made vertical farming viable and investigate just how much climate savings Bowery can be expected to wring out as it grows in scale.

Lettux

We can’t understand Bowery without describing BoweryOS. It’s the secret sauce that ties its automated systems, sensors and data collection together into a central nervous system. The company is tight-lipped about specifics but notes that it unlocks the ability to rapidly replicate its growth system at new farms.

“You could be the greatest farmer in the world in Salinas Valley, and I pick you up and bring you to New Jersey and that knowledge doesn’t transfer,” says Irving Fain, founder and CEO of Bowery Farming. “You put the Bowery operating system inside of that farm, and that farm now has the knowledge and understanding of every crop we’ve ever grown and every process we’ve ever run immediately available to it. In essence, what we’re really doing is building a distributed network of farms, whereby every new farm that enters that network benefits from the collective knowledge of the network that came before it.”

Tech and VC heavyweights join the Disrupt 2025 agenda

Netflix, ElevenLabs, Wayve, Sequoia Capital — just a few of the heavy hitters joining the Disrupt 2025 agenda. They’re here to deliver the insights that fuel startup growth and sharpen your edge. Don’t miss the 20th anniversary of TechCrunch Disrupt, and a chance to learn from the top voices in tech — grab your ticket now and save up to $675 before prices rise.

Tech and VC heavyweights join the Disrupt 2025 agenda

Netflix, ElevenLabs, Wayve, Sequoia Capital — just a few of the heavy hitters joining the Disrupt 2025 agenda. They’re here to deliver the insights that fuel startup growth and sharpen your edge. Don’t miss the 20th anniversary of TechCrunch Disrupt, and a chance to learn from the top voices in tech — grab your ticket now and save up to $675 before prices rise.

Injong Rhee, who joined Bowery as CTO in February, and who like the company’s chief science officer is a Samsung expat, tells TechCrunch that density is the true secret to Bowery’s success. The company says it’s around 100 times more productive in its footprint than traditional growth, and BoweryOS is a big piece of that density.

“Because of this density, it’s really almost impossible to actually have everything manual,” says Rhee. “We automate almost every part of the growth and processing, and that actually creates that efficiency that we’re looking for. This is all connected to an automated movement system.” Robots will whisk away plants at just the peak moment of their taste, only to replace a grow tray with a new crop of seedlings.

Bowery’s big bet — and in many ways, it remains just that, a bet — is that the tacit knowledge passed down from farmer to farmer over generations can now be turned into experimentally backed processes coded into the software that powers every stage of a plant’s life cycle. The company can effectively plug and play BoweryOS into new farms as they’re built, readying the company for rapid horizontal scaling.

Much of the company’s ability to develop this system lies in its control over the growth facilities. The challenges of outdoor farming are legion: Insects require insecticides, storms require runoffs and ditches, and droughts require careful hydrological conservation initiatives. The techniques required one year may go unused the next as each harvest cycles through.

Bowery, on the other hand, knows precisely every detail of its growth space either by design or via sensors, which makes the tech much more programmatic and ultimately achievable.

That said, is it real? It certainly felt real as I was standing in Bowery’s Farm Zero and Farm One, watching thousands of plants growing in real time with the occasional robot appearing.

Yet, the company’s key innovation is combining off-the-shelf components together into a useful whole, and the defensibility of that is far harder to judge for this humble external observer (and Bowery takes pains to keep certain technologies and products out of eyeshot). A patent search showed little in the way of granted intellectual property, with the company’s sole patent focusing on its product packaging.

How lighting LED the future of agriculture

Unsurprisingly, the hardest input to acquire for indoor farming happens to be one of the most abundant: sunlight. Lighting is everything to a farm, vertical or otherwise, and Fain cited LED developments as the key technology that allowed Bowery to get under way.

“There will be a revolution,” Purdue University horticulture professor Cary Mitchell commented in 2014. “I think that in a decade’s time, LED will become the de facto lighting source for controlled-environment agriculture.”

As Mitchell’s work noted at the time, LEDs were significantly more efficient than the HPS (high-pressure sodium vapor) lights traditionally used for indoor growing, resulting in a dramatic reduction in energy costs. They’re also easier to control and emit far less heat, so they can be placed closer to the plant. It was a remarkable breakthrough for an application so far afield from their intended use.

“The LED, when it was first developed, nobody thought [that] this is going to be their use case,” Rhee tells TechCrunch. “They used it on TVs and phones. That has really driven the cost of those LEDs down. And that actually enables the applications like this.”

Fain cites Haitz’s law, a concept similar to Moore’s law, that maps the rapidly increasing performance and decreasing price of LEDs. “[P]rogress in LED performance has been so rapid that it has been described by a logarithmic law, akin to Moore’s law for microelectronics,” Nature noted in 2007.

“[T]he law forecasts that every 10 years the amount of light generated by an LED increases by a factor of 20, while the cost per lumen (unit of useful light emitted) falls by a factor of 10.”

Fain adds, “We’ll see even beyond what we saw about 10 years ago, another 50% to 85% drop in the cost of the fixtures, and we’ll see another doubling or so of efficiencies. The trend that got us to here is going to continue moving us forward.”

LED developments went a long way toward validating Fain’s early vision, and it’s a pattern that has repeated across many other components as well.

“We’ve solved most of the technical problems of how to grow food indoors,” vertical farm pioneer Dickson Despommier tells TechCrunch as he narrates the last decade of developments in the field. “It gets better and better as companies like Phillips, a lot of the Japanese LED light companies put their nose to the grindstone and came up with tailor-made lighting per crop. So, whatever you want to grow, you can grow it optimally because we can tune these LED lights, and that’s already available, so you can get it. Nutrient solutions, no problem. None of this is a problem.”

Balance of power

For all those technology improvements, skeptics still question whether the current state of vertical farming is ultimately an environmental net positive. “The energy-balance-physics are not controversial, but none of us likes to acknowledge the inputs when silver bullets give us so much hope,” Bruce Bugbee, professor of crop physiology at Utah State University, said in an email to TechCrunch.

“The electric energy to run the lights (not including the air conditioning costs) to grow lettuce in NYC is four times greater than the energy cost to grow lettuce in southern California and ship it to NYC in a refrigerated truck,” Bugbee notes.

“It requires more than two acres of solar panels to get the energy to run the lights for one acre of food production. If we stack the food production layers tenfold, then it takes 20 acres of solar panels. And this is with the most efficient solar panels and the most efficient LEDs.”

Bugbee’s position isn’t so much that of a critic as a pragmatist — an important voice to have in a conversation weighing the pros and cons of a new technology. Prior to speaking with him, I certainly viewed the world of vertical farming with a healthy dose of skepticism from the moment I entered Bowery’s Farm Zero, its original facility in Kearny, New Jersey. When you walk into one of these big, opaque buildings, it’s hard to shake the notion that vertical farming today is blocking crops from accessing Earth’s largest free renewable energy source.

In a 2016 piece, Stan Cox, a senior researcher of ecosphere studies at The Land Institute, breaks down some of the biggest questions that came up as vertical farming was entering the cultural consciousness here in the States.

The energy efficiency of lamps or production systems can be improved, but not infinitely, so indoor crops will always be heavily dependent on electricity and other industrial support. That means that with every kilogram of food we produce under artificial lighting, we will have passed up an opportunity to harvest free sunlight and will thereby contribute to the Earth’s warming.

“We take our sustainability commitments really seriously, and I will never tell you we’re all the way there,” Fain said. “In fact, I’m not sure as an entrepreneur there is such a thing as all the way there, and I always say if I ever feel like I’m all the way there, I should probably retire and ride off into the sunset then — or the LED set, whatever it would be.”

He sees the problem as a miscalculation about the usage of the sun. “The mistake sometimes made is this notion when people talk about, ‘Well, the sun’s out there and it’s free, right?’” he explained. “So is the sun free? Of course, it is … but if you think about the totality of the food supply chain … the sun actually has a cost. It’s just that cost is embedded in different parts of the supply chain in the food system than the way you see it in what we’re doing at Bowery.”

Like other champions of the technology, Fain insists the system be viewed in totality, citing its reduction of pesticides, water usage and soil erosion, among other points. Bowery is also actively pursuing renewable energy, relying on hydro to power its Maryland facility, coupled with other sources.

He concedes that powering an indoor farm entirely with solar power is difficult — or even impossible — given current infrastructure. But the CEO once again invokes Haitz’s law and the role it could play in continuing to reduce LED power consumption.

“As the lights keep [getting] more and more efficient, less and less heat is generated, and so less energy is required in HVAC,” says Fain. “So as time goes on, not only is renewable energy going to be more ubiquitous and cheaper, which I think is a reasonable assumption at this point, but the energy requirements overall from our farms are going to be lower.”

There are still a lot of question marks, which, to be fair, is expected with such a young industry. Crop diversity beyond lettuce and other leafy greens is one. The definitive math behind whether it’s ultimately a climate net positive is another.

The doomer in me would quickly point out that simply growing leafy greens indoors will likely never move the needle on our climate catastrophe as much as simply getting people to reduce their meat consumption. But just because there are bigger problems to solve doesn’t negate the importance of addressing the smaller ones. Every solution is a piece in the broader climate puzzle.

If technology is one potential moat for the company, the other is building up a recognizable consumer brand so that grocery shoppers will pick its plastic clamshell in the produce department. So Bowery Farming’s finances, marketing and competitive landscape is where we turn to next in the fourth and final part of this TC-1.

Bowery Farming TC-1 Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Produce development

- Part 3: Agtech engineering

- Part 4: Branding, finances and competitive landscape

Also check out other TC-1s on TechCrunch+.