Unparalleled contrasts have marked the last decade and a half — from the devastating plunge of a major housing crash to the soaring heights of the longest bull market and the unforeseen havoc of a global pandemic. Amid these turbulent times, the VC accelerator industry has emerged as a stalwart player.

Fueled by a zero-interest landscape in 2020, it has surged, giving rise to an ever-growing array of funds. That said, a paradigm shift of the broader venture landscape could be on the horizon.

Starting a tech company today costs 99% less than it did 18 years ago when Y Combinator was started (today and 2005), largely due to the emergence of cloud technologies, no-code tools, and artificial intelligence. There is an unprecedented amount of information or knowledge that is now freely available to guide founders (e.g., the free YC Startup School courses).

Network effects have evolved, moving away from the traditional physical spaces to digital ones. Digital communities and social platforms such as Twitter, Signal NFX, YC’s co-founder matching, and Slack communities (e.g., Flyover Tech) have played a significant role in this shift.

At the start of 2022, there were $1 trillion in assets under management (AUM) and $230 billion in VC dry powder, figures that dwarf the prefinancial crisis AUM by a factor of five. Concurrently, the number of funds raised in the eight-year period up to 2022 was 2,700, up from 883 in 2010. Crowdfunding witnessed a 2.4x growth from 2020 to 2021.

Angel investments in 2022 equaled those from 2006 to 2011 combined. Family office investments increased by 5x, and corporate venture investments rose 6x, thus opening new capital avenues for founders who found it difficult to raise capital.

The competitive landscape also underwent significant changes. At the dawn of 2022, there were 2,900 active VC firms, marking a 225% increase since 2008. This influx of funds has propelled platform VCs to step up their game, nurturing their portfolios and winning deals more aggressively.

Finally, the talent pool for tech startups has broadened immensely. Factors such as remote work, offshore development, and the steadily growing labor pool of software engineers have enabled startups to hire additional engineering talent, adding yet another catalyst to this vibrant ecosystem.

Importantly, the traditional accelerator model has enjoyed the fruits of these potential paradigm shifts. The number of accelerators has more than doubled since 2014, while the number of accelerator-backed startups in the U.S. has nearly quadrupled in the same time period (investments from 2005 to 2015 and total investments through 2021). However, as we look into the future, founders must confront a key question: Are there too many accelerators now, and is joining an accelerator even needed anymore?

Accelerators are facing competition on all sides

The idea that accelerator funds have little value grew in popularity during the pandemic, as capital was so abundant that first-time founders began bypassing accelerators altogether. Moreover, rumors of deeply unethical behavior at accelerators are starting to surface frequently. The most notable example was allegations of fraud at Newchip, a popular virtual startup accelerator.

The liquidation of Newchip sent ripples through the startup ecosystem as perceptions of grifting at accelerators gained momentum online. Another instance of negative press involved the On Deck accelerator, which laid off 25% of its staff in 2022. The layoff came from a deal that went sour with Tiger Global, forcing On Deck to use its Series B funds to keep the lights on in the accelerator.

Founders must confront a key question: Are there too many accelerators now, and is joining an accelerator even needed anymore?

The fall of players like Newchip and On Deck are not isolated incidents. They testify to the growing realization that accelerators increasingly compete for capital and opportunity with other established, institutional VC firms. For example, when YC was founded in 2005, a “pre-seed” round did not exist, and it cost $500,000 to start a tech company. Now pre-seed rounds have surged in popularity to being the most popular round for getting your business from MVP to $1 million+ ARR. In 2022, there was 10x the amount of capital in the market than a decade ago, with hundreds of pre-seed VC funds in existence with hyper-targeted theses (e.g., psychedelics or construction).

The influx of pre-seed venture dollars in circulation has increased competition with accelerators and influenced more funds to pursue a “platform VC” model, with some even having a venture studio (e.g., building companies in-house) or incubator (e.g., long-term support at the earliest stages). In some cases, funds themselves launch “accelerators,” which in most cases are the platform support and capital extended to earlier startups, so the VC invests earlier.

Importantly, a VC firm pursuing pre-seed funding escapes the traditional stigmatized accelerator branding due to more favorable terms. Furthermore, many VCs have also built communities around their accelerator model in ways traditional accelerators fail to. Thematic platform VCs have world-class advisors for specific sectors and create cross-pollination within their portfolios. Some pre-seed VCs are focused on backing community-driven startups that have access to communities, hacking distribution and discovery.

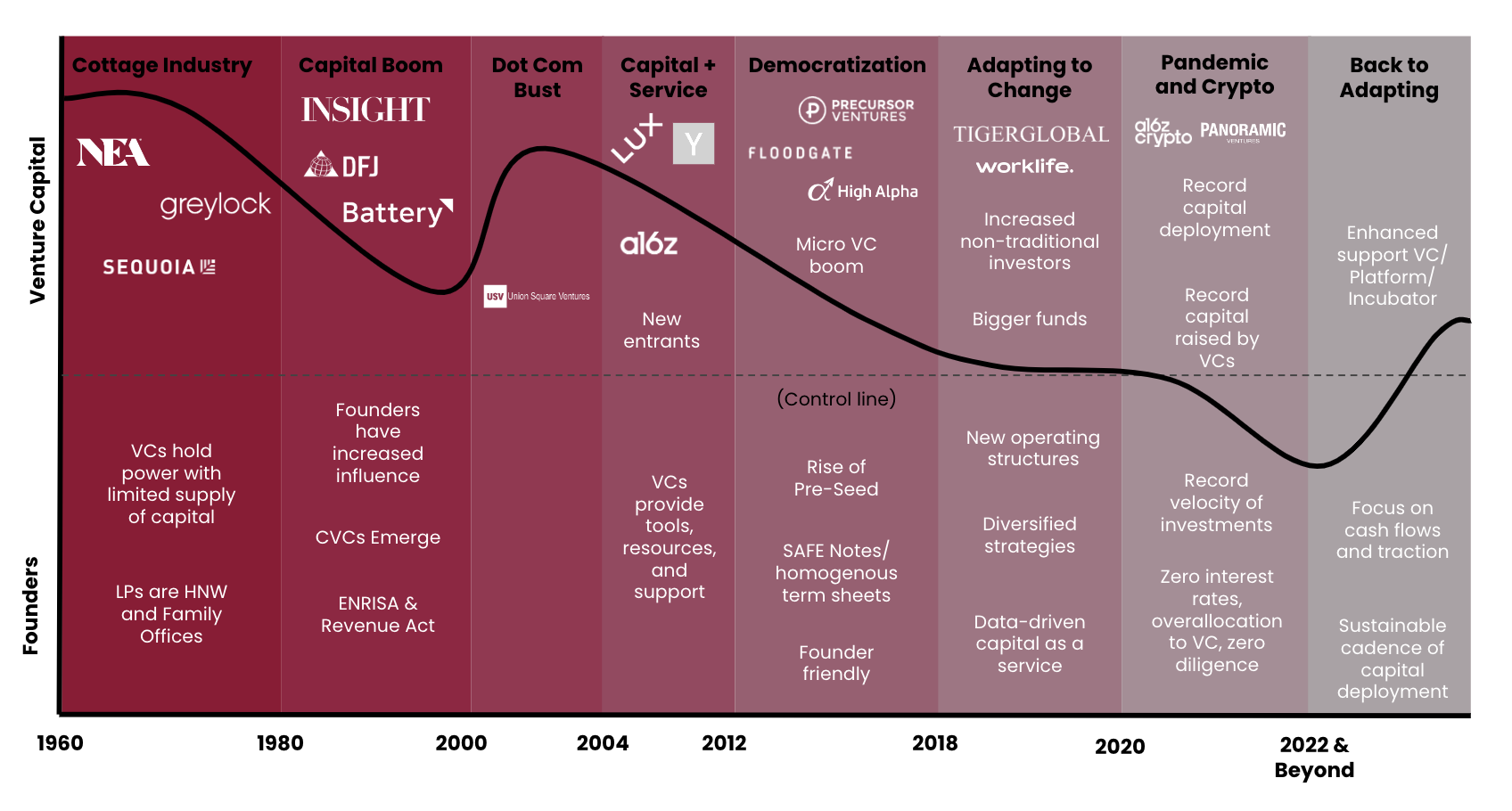

That said, it’s not just micro VCs or emerging managers who are launching platforms; brand names are, too. For example, Sequoia Capital’s Arc or a16z’s Crypto Startup School attracts quality with favorable terms, capital, and a strong brand. The chart below shows how VCs have adapted through market cycles:

Image Credits: Brett Calhoun

Platform VCs vary in both definition and focus depending on the logistics of the firm. For example, at Redbud VC, our team manages a VC fund plus some aspects of a studio, including support from world-class operators who have founded billion-dollar companies. In general, VCs have continued to invest earlier, with many now backing idea-stage or pre-product founders. Some firms like K9 Ventures won’t even back founders who have taken prior institutional capital. Due to the increased competition from the platform role and the hunt for untapped early-stage founders, every VC will soon have a platform or studio component.

Are accelerators giving founders what they need and want?

All this said, what is different about an accelerator versus a platform VC, strategic angel, or an early-stage VC in general? If we drill into what an accelerator does for founders, generally speaking, it can be bucketed into:

- Knowledge sharing.

- Networks.

- Resources.

- Peer groups.

- Capital.

- Events.

The value of the above is directly correlated to the level of entrepreneurial experience the founder possesses. That said, the value accelerators provide comes at a cost: time and equity. The large equity stakes and extensive work can be a repellant to quality founders. If the value is delivered, the equity can be argued, but the time cannot. Some accelerators are adding 20+ hours of programming per week and networking events that may be lackluster.

In Redbud VC’s conversations with 2,000+ founders, our team found that what is truly relevant to founders is network effects and knowledge sharing. Founders are time-strapped, so filtered feedback from successful founders can expedite years of learning, and warm intros can save months.

PitchBook’s recent study quantifies the success of accelerators after interviewing founders and obtaining data from five of the leading accelerator funds: Y Combinator, Techstars, SOSV, MassChallenge, and 500 Startups. The top three biggest asks from the founders were:

- Better VC introductions.

- More warm introductions to potential customers, including enterprises.

- Education on how to run a company.

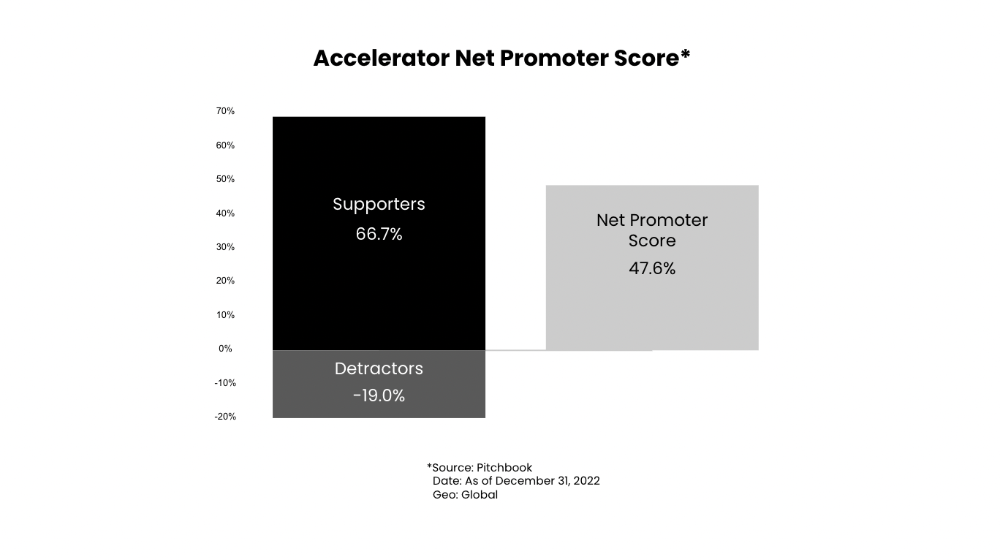

What is concerning about this feedback is that these areas of required improvement are precisely what accelerators are supposed to deliver. Further validating this troubling reality is the average accelerator’s Net Promoter Score (NPS) of just 47.6%. This is a relatively low NPS on a scale of –100 to +100 for a bespoke service that should change the trajectory of an entrepreneur’s career. This begs a very important question: Do accelerators really deliver better than traditional VCs?

Image Credits: Brett Calhoun

The power of Y Combinator

One area where accelerators have delivered on their promised value is helping founders raise a follow-on round of capital. In fact, over 50% of founders who completed an accelerator raised a follow-on round of funding. Each subsequent round raised by a founder increases the chances of exiting, which is displayed in the data from PitchBook. YC and Techstars founders had the highest rate of raising subsequent capital and also had the highest rate of exiting at 18%. Although somewhat misleading, YC’s cumulative exit value of $93 billion in the 2012 cohort exceeds the other four accelerators’ exit values combined between 2010 and 2020.

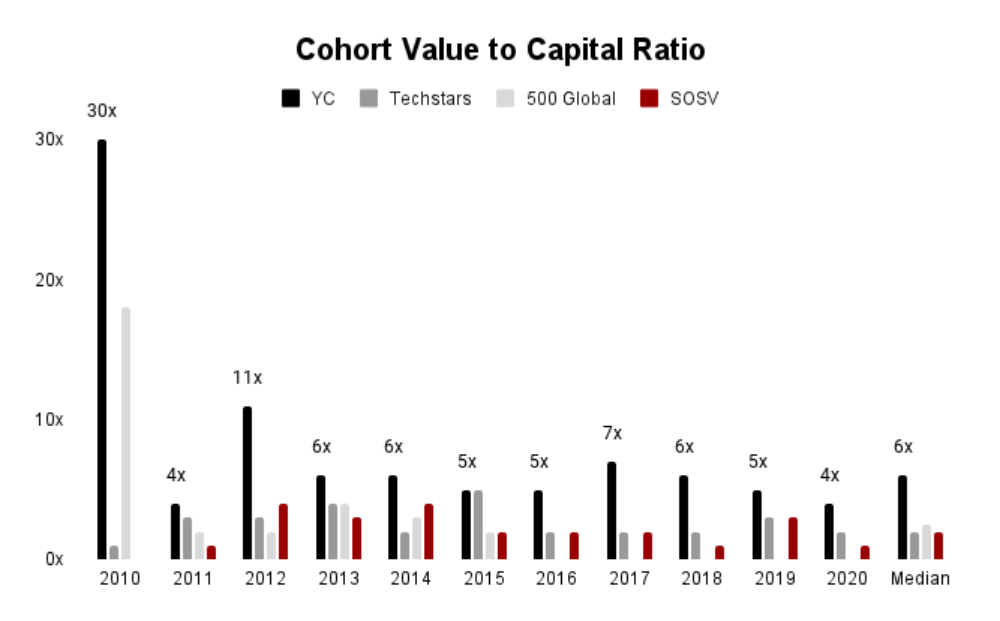

In addition, the cohort value to capital ratio is significantly higher at YC, with a median of 2x to 3x all other accelerators.

Image Credits: Brett Calhoun

An even more impressive data point is that YC’s rate of unicorns is 4.5%, which is 4x to 20x higher than the others. YC may have the highest hit rate of unicorns of any investors, accounting for ~8% (YC unicorns/total) of all unicorn startups created globally. Lastly, the most intriguing stat is YC’s resilience with unicorn creation, as all other accelerators nearly went to zero between 2016 and 2020:

Image Credits: Brett Calhoun

This data is unsurprising, as YC is broadly accepted as the best accelerator globally. Here is what YC does that no other accelerator can offer:

- A brand-boosting value, eternally, similar to attending Harvard or Stanford.

- Hacking the strongest network effects in the world.

- Biggest distribution engine to first customers.

There are even funds that invest solely in YC companies, similar to those that only invest in Stanford students and alumni. Although YC is an accelerator, their success might not be because of the accelerator but because they have made good picks. To back this data point, their first fund is probably the highest-performing fund in YC history, with estimates saying they turned $11.2 million into $3.6 billion.

What is relevant about this data point is that YC’s first fund did not have the resources or network effects that it does now, yet it has had the highest rate of return. This suggests that YC was founded by great pickers who have built a prestigious brand around one of the greatest communities.

YC’s brand attracts both first-time founders and exited founders. Many accelerators have tried to differentiate themselves and attract higher-quality sector-focused talent by partnering with corporates, but according to CB Insights, “60% of corporate accelerators fail within two years, and partnerships result in less than 1% of the time.” Even though the YC brand gives companies a premium valuation for follow-on capital, it generally doesn’t recoup even half of the 7% taken for $125,000, so it’s unclear if the cost is “worth it.”

Partly due to the success of YC and the early success of others, there were over 8,000 accelerators worldwide as of 2020. More than half of the accelerators were started between 2014 and 2020. The influx of accelerators has diluted the quality of mentors and network effects per accelerator. Due to this, many founders have had bad experiences with accelerators. High-quality founders have repelled the diluted branding for accelerators, as they don’t need to give up large equity stakes for the value they provide or believe they are too good for an accelerator. As founders move away from accelerators, they have been forced to pick from a lower-quality talent pool.

The future of the accelerator model

Market conditions have a deep impact on the value accelerators provide. Market downturns are good for accelerators, and bull markets are bad. In bull markets, there is an increased propensity of buying by consumers and businesses, making it easier to sell, and an abundance of capital in the market, making it easier to raise. Therefore, bull markets decrease the value that accelerators offer. Conversely, founders flock to accelerators in a downturn as capital dries up elsewhere. The next question is, will accelerators be around in 10+ years? Below are two suggested scenarios for how this plays out.

- Nearly every early-stage VC will have a “platform” component to supporting early-stage founders, eroding the value of most accelerators. Due to this, YC, which arguably has the best network effects in the market, will be the last accelerator standing as the race to early-stage intensifies.

- As the competition for early-stage investing intensifies, VCs struggle to differentiate themselves. Therefore, there will be fewer new funds, and existing funds will struggle to raise subsequent capital. The decrease in early-stage funds will increase the value of accelerators. In addition, many recent unicorn founders will exit, boosting the returns of accelerators and maybe joining their alma mater accelerators as partners or advisers, further increasing their value.

In scenario one, continuous innovation with new platform VC models will continue to beat accelerators with a higher value-to-equity ratio. The increased competition with new and expanding funds will diminish the quality that accelerators can attract, making them unattractive investment targets for LPs. That said, YC will still hold its value-to-equity ratio with a continuous 10x-ing of network effects as its portfolio companies continue to grow and exit. In the end, YC could be the last pure accelerator standing. It would take years to realize the diminishing effects on accelerators because it takes 5+ years to realize the success or failure of a cohort.

The question is, how long will it take for the quality to diminish? There has been an intensified rate of unicorn startups founded in the last five years, which will lead to successful exits and more operators founding or joining funds to support founders (e.g., the founder of Flexport just joined Founders Fund). Also, YC is the only accelerator actively producing unicorns in the last five years. Scenario two notes that some successful founders may exit and then join or advise their alma mater accelerator but could also be competing with funds they start (e.g., Willy Schlacks, YC alum, starting Redbud VC).

In the second scenario, LP capital decreases for VCs as many fail to obtain returns even competitive with the S&P 500. The zero-interest-rate period of 2020–2022 increased investment in venture capital, and the abundance of capital increased the velocity of investments and decreased diligence. Now there is more capital than ever in early-stage VC, pushing pre-seed/seed valuations higher, making it more expensive for funds to hit ownership targets. Dull returns and high interest will deter LPs from VC.

That said, scenario two is already being publicly acknowledged after a recent article by Vice, which included many quotes from VCs. For example, Albert Wenger of Union Square Ventures said, “LPs are way over-allocated to venture.” In addition, multiple notable funds have missed their fundraising targets (e.g., Tiger Global) or have shut down (e.g., YC’s late-stage fund). In fact, pre-2016 vintages are returning 40% to 240% more capital than post-2016 vintages over the same time period. In the long run, there will be fewer early-stage funds in the market. The decrease in early-stage funds will increase the need and value for accelerators.

That said, accelerators must continuously iterate on how they compete for and attract early-stage investments. This will require accelerators to add value to the ecosystem and add value to investors because, at the end of the day, the customer is the investor. If they are not providing returns, they will stop funding. Accelerators must adapt to the changing environment or forgo supporting founders.

Regardless of whether either scenario happens, the competition forces investors to provide much more than just capital. Although this is good, founders must have a strong filter for who is bullshit and who will roll up their sleeves. Similar to how investors do customer discovery, founders should do investor discovery.