The U.S. Senate earlier this week approved the CHIPS Act, which includes $52 billion to subsidize domestic semiconductor production. It still has to struggle its way through the bureaucracy (here’s a quick refresher), but clearing the Senate is a huge and important step toward the American chip fabrication industry getting a serious chunk of cash.

Personally, I’m psyched that this may be happening for a few reasons. Yes, yes — supply chain problems and chip shortages have been the bane of everyone’s life for a hot minute, and onshoring some of these fabrication materials, tools and know-how will go a long way toward making the U.S. less reliant on external manufacturing and more resilient in general.

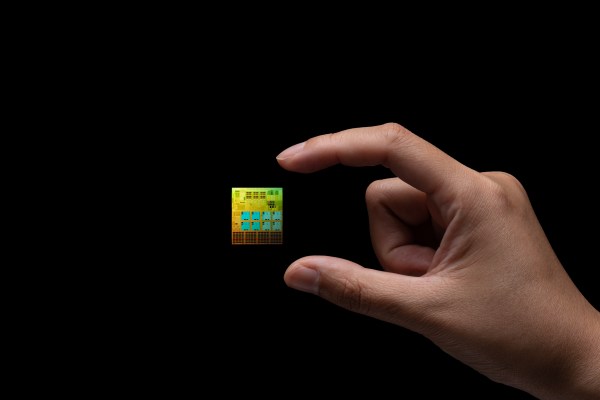

That’s all good and well, but let’s be honest: $52 billion isn’t exactly a sachet of coppers and nickels, but chip manufacturing is expensive. The last planned chip factories I can remember are the $19 billion plant Intel is building in Germany and the $20 billion plant the company is building here in the U.S. If that’s the price tag of a factory, the subsidy builds two and a half plants. That means jobs, but it doesn’t exactly turn the U.S. into a chip-fab juggernaut overnight.

Far more than new factories, I’m most excited about the possibility of history repeating itself. Intel’s choice to build a $20 billion chip fabrication facility in Columbus, Ohio, along with the more recent news of the potential cash injection into the industry, could set the stage for a startup ecosystem boost.

How Silicon Valley came to be

Silicon Valley itself became possible when a few important things happened in the 1940s. The seed of it all was professor Frederick Terman’s work in the engineering faculty at Stanford University. He was working on radio engineering and had a specialty in circuits, vacuum tubes and a bunch of other innovations. During World War II, the military funneled a bunch of money his way to help a Harvard team develop technology that would help with the war effort, and after the war, he went back to Stanford, establishing the Stanford Industrial Park (which later became the Stanford Research Park).

All of this is to say that the war fueled research, which attracted money and talent. From there, it became easier and easier to find the right people to start companies with. On top of that, in 1969, Venrock — the Rockefeller family venture firm — became the first thing that we would recognize as a venture capital today.

But the real genesis of Silicon Valley was Fairchild Semiconductor — yes, the same semiconductor industry that the Senate is now dangling a $52 billion carrot in front of — and the many talented engineers it trained and cultivated. The company spun out of Shockley Semiconductor Labs, which was widely recognized as the OG Silicon Valley tech company. The company had a huge impact on tech, but it marked a lot of other firsts, too, including arguably being the world’s first venture-capital-backed company.

Amazingly, Shockley’s founder tried to hire some of his ex-colleagues from Bell Labs, but none of them fancied a move from the East Coast to California. So he did something revolutionary at the time: He founded a new company with a bunch of fresh engineering graduates. These graduates climbed through the ranks, found their own specializations and evolutions, and ended up getting the hell out of dodge, spinning out a bunch of new companies. (Some of these individuals, known in Silicon Valley lore as the “traitorous eight,” left Shockley to found Fairchild and were later directly involved in founding Intel, AMD and Intersil, three of the biggest influences on semiconductor and chip design and manufacturing.)

Shockley Semiconductors, incidentally, was the first semiconductor lab that started using silicon to manufacture chips — instead of germanium — revolutionizing the industry. And this shift of materials did something else, too — in 1971, the nickname “Silicon Valley” was coined.

After World War II, the Cold War drove an enormous technology push; radar, microwaves and satellite tech all needed electronics. NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory was founded before the war, adding a new generation of engineering to the local ecosystem. Lockheed Martin opened a plant in Silicon Valley, attracting employees from all over the country, adding a lot of aerospace and propulsion tech skills and knowledge to the mix.

A university that attracted bright-eyed and bushy-tailed students to California, molding them into technology innovation mavens to populate the workforce, was perfect for the handful of successful R&D-driven technology innovation companies that popped up around the same time. It became a true ecosystem: Senior staff spun out new companies. Engineers got valuable work experience. The new tech generated tremendous wealth, some of which was reinvested in the ecosystem. Angel investments became a thing. Corporate venture capital became a thing. And venture capital became a whole asset class that — for better or for worse — fuels the entire tech ecosystem.

Why government investment matters

Venture capital is largely reactive in five- to 10-year cycles. Governments have the power to incentivize and set policy that has impacts far beyond that window of time.

Silicon Valley wouldn’t have happened if it hadn’t been for a complex interplay between Cold War-era research, skills, knowledge and a lot of cash flowing into the region. A $52 billion stack of cash would found a lot of early-stage startups, of course, but the truth is that most startups have neither the knowledge nor the infrastructure to take grant money from the federal government. Most startups do not have the infrastructure, staff or skills to be able to spin up hardware manufacturing at the scale or complexity needed by the wider ecosystem. I should name, as well, that exceptions do exist — there are, indeed, companies building electronics domestically. One example is Tempo Automation; it doesn’t make its own chips, but it is doing quick-turn printed circuit board assembly right here in Silicon Valley.

I expect that midsized companies and corporations will gobble up most of the money that becomes available. I’m not here waxing lyrical about corporate trickle-down economics, but there’s a real, positive impact on the tech ecosystem.

Founders who are starting companies in the semiconductor space were just given hope for a significant boost. The companies are suddenly worth a lot more; those 52 billion dollars will get spent one way or another, and on the whole, an ongoing commitment from the feds that this country wants to refocus its attention on domestic manufacturing is good news for jobs, knowledge transfer and encouraging a new generation of young engineers to learn how to design and manufacture hardware. Startups continue to play an important role in the ecosystem; a lot of corporates treat the startup ecosystem as an outsourced, high-risk, high-innovation R&D team.

I expect that a renewed interest in semiconductors on U.S. soil will shake loose a lot of interest and open a bunch of new opportunities, perhaps especially for deep tech companies spinning out of academic research. Those weird theories you were studying as part of your Ph.D. thesis? Now’s the time to dust ’em off. If you needed a sign, this is it. This is the sign. Go build, and raise as much money as you can, while you keep your fingers crossed that the 2024 election doesn’t do a complete policy about-face.