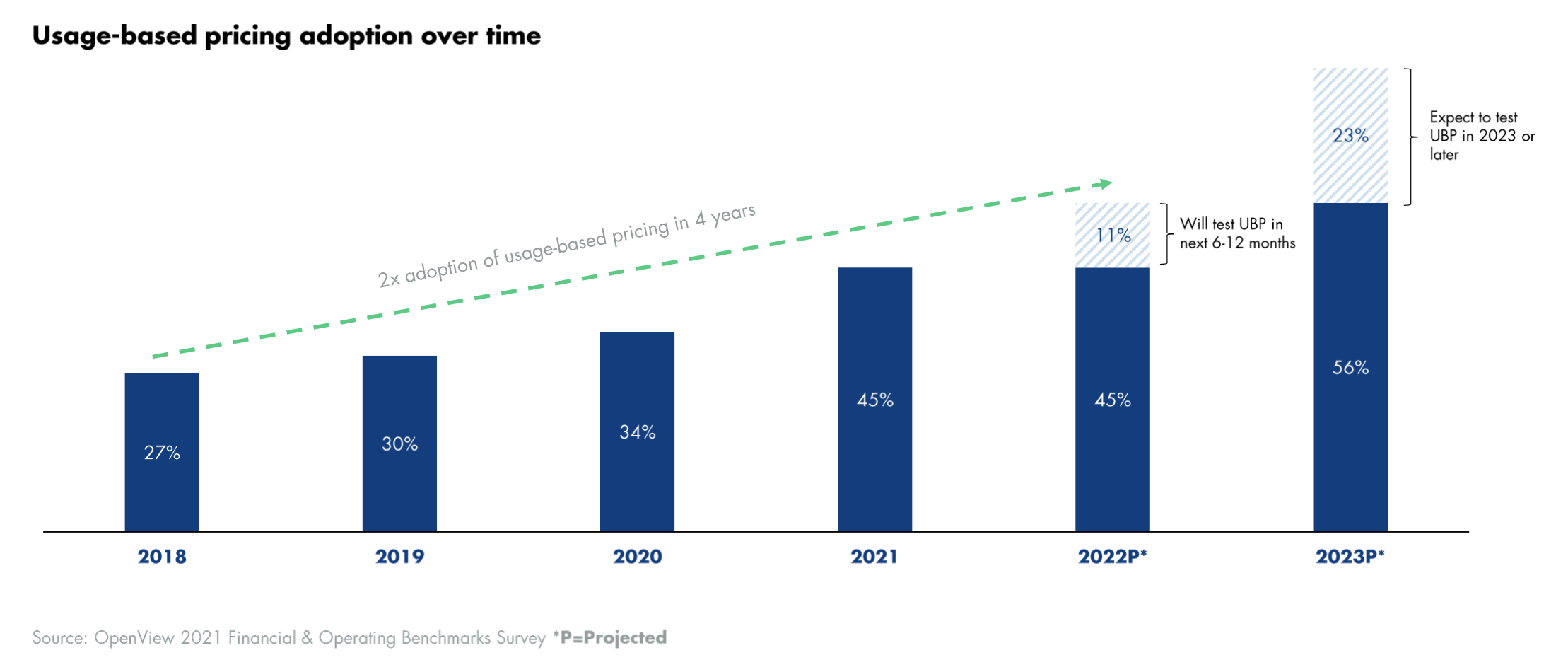

Is usage-based pricing (UBP) going mainstream? That may be so, if you consider the results of Boston-based VC firm OpenView’s annual Financial and Operating Benchmarks survey. Of the nearly 600 SaaS companies that responded, 45% say they are using this flexible pricing model, up from 34% in 2020.

The survey also looks into how companies that adopt flexible pricing models perform compared to their counterparts, and how it impacts them more broadly. And since it doesn’t shy away from mentioning challenges, we felt it would be relevant reading for founders who might still be on the fence.

To get a deeper look into the results of the survey, we spoke with OpenView operating partner Kyle Poyar, who has championed usage-based pricing models in the past and co-authored the firm’s 2021 State of Usage-Based Pricing Report with partner Sanjiv Kalevar.

“Usage-based pricing is an incredible message that you stand behind your products, and you truly believe your customers are going to be successful.”

The main insights are below, but before we jump in, here’s a note on definitions: the report’s definition of usage-based pricing adoption includes companies like Twilio, whose pricing is almost entirely pay as you go, as well as those offering subscription tiers based on usage, like Zapier.

In other words, the report’s co-authors don’t draw the line at whether there’s a subscription element; instead, they consider if pricing is tied to product consumption behavior, as opposed to just seat-based pricing in a landscape where companies also charge based on customer size, functionality, services or other factors.

Why the seats are empty

One of the factors driving this shift is that charging for “seats” makes less sense than it used to, according to OpenView. Poyar noted that the value a customer receives rarely ties in directly with how many people log in, especially as more and more startups now offer solutions built around automation, AI or APIs.

“In fact,” he said, “it might even be negatively correlated: When AI can automate tasks, the more successful the solution is, the fewer people need to be logging in. So seats are just an outdated way of charging and don’t allow a company to communicate value or invest in features that would add more value.” While Poyar admitted that not every company does this, he pointed out that automation, APIs or AI often play a big role in the success of the companies going public today.

This might explain another shift in thinking: Many companies that go public “are calling out usage-based models and making it a focus of their S-1s or of their investor materials,” Poyar said. He added, “There used to be a fear that investors would penalize them for a usage-based model, because there was a fear that it wasn’t recurring revenue, and it wasn’t predictable. [ … ] Now, a usage-based revenue model is seen as a competitive advantage, and a driver of long-term growth.”

This shift in perception might be recent, but the trend itself is a result of software buying evolving over the last decades, Poyar and Kalevar said. As the report makes clear, and we agree, the buying process is often driven by the end user, with SaaS companies adopting product-led growth, an approach that OpenView champions and is heavily represented in its portfolio.

Better metrics driving adoption

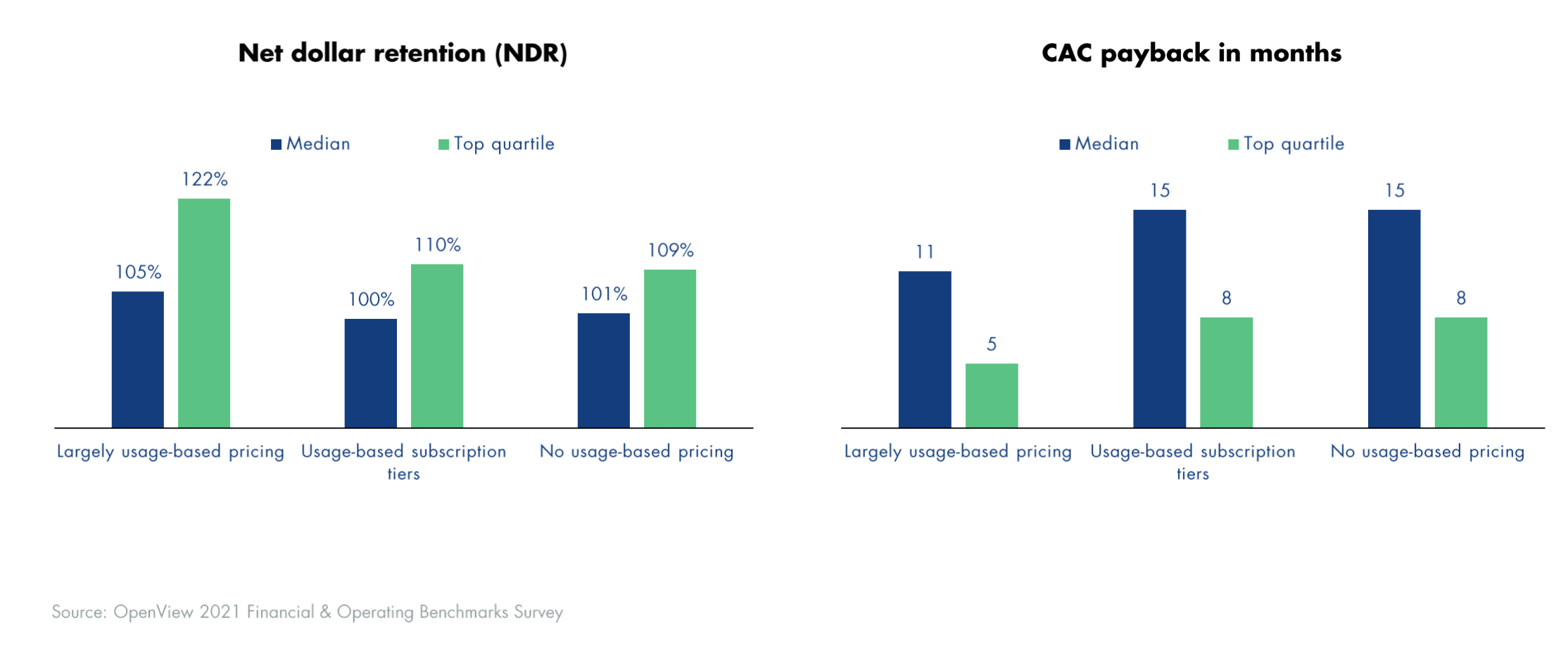

If investors have come to love product-led growth and usage-based pricing, it’s at least in part because the companies that adopt these models outperform their peers. According to OpenView, they have both higher net-dollar retention (NDR) and faster cost of customer acquisition (CAC) payback.

Image Credits: OpenView

This is based on a survey sample that included companies with various levels of annual recurring revenue, but a look at recent SaaS IPOs suggests that “publicly traded SaaS companies with the best NDR also have a usage-based model,” the report said.

Usage-based companies’ superior performance is corroborated by recent data from investment firm Battery Ventures. In its State of the OpenCloud 2021 report, it attributed higher NDR, superior sales efficiency and better overall metrics to companies using consumption-based (or pay-as-you-go) pricing, compared to traditional subscription-based ones.

The saying goes, “correlation is not causation,” but Poyar feels otherwise based on his own experience: “When I have worked directly with our portfolio companies around implementing a usage-based pricing model, it’s not uncommon to see growth accelerate by 15%, 20%, 25%. So while I can’t extrapolate for every company, that gives me conviction that there really is true incremental growth from pricing changes.”

With that context, it is easier to understand why companies are now, as Poyar puts it, “shouting from the rooftops that they charge based on usage” — and more generally, why adoption is growing.

More and more adoption

As we mentioned earlier, 45% of the 600 companies surveyed already use UBP, but here’s more data to back up the “UBP is going mainstream” hypothesis: 11% are planning to test it in the next 6 to 12 months and another 23% plan to do so from 2023. “The data from this year’s report proves that there is an appetite for usage-based pricing, and we expect this to continue to accelerate in the coming months,” Poyar said.

Image Credits: OpenView

But switching to a new pricing model overnight can be terrifying, and companies need to properly test if and what form of usage-based pricing can work for them.

Poyar has some ideas for companies looking to test: “The first thing that most companies probably aren’t doing enough of is just doing offline testing. So doing research surveys, interviews of their customers, which gives them a lot of great insights — essentially, the insights that they would get from a live test, without the disruption of actually changing pricing on your customers.”

If you’re launching a new product, Poyar advises allowing existing customers to use that product to a certain extent before charging for additional usage. Companies that have a free offering should ensure that there’s a usage cap, just like Zoom did with its 40-minute limit for free group meetings.

The report also includes suggestions for pricing structures that will give customers “greater peace of mind,” based on examples from Twilio, Snowflake, Datadog and AWS. Indeed, perceived unpredictability is still a challenge for such pricing models, especially if the customers are enterprise-sized.

But even that is changing, Poyar told TechCrunch. “Procurement is increasingly changing their mindset as well, [and catching up],” he said. “You might have seen that the GSA Schedule, which is the government purchasing schedule, is amending their rules to allow folks to buy on a consumption basis, which was never allowed before. They realize this is a best practice so that they’re not paying for shelfware and that they have better alignment between the value that agencies see and the price they pay for software.”

Alignment is one of the key advantages enabled by UBP, he said: “Usage-based pricing is an incredible message that you stand behind your products, and you truly believe your customers are going to be successful. And if they’re not successful and using, they’re not going to pay for it.”

Companies with a usage-based model tend to have a better customer experience, he says. “They’re more focused on that everyday usage among their customers, because that’s their lifeblood. And so usage-based companies are just better positioned in the long run.”