History of The MP3

How An Algorithm Transformed The Music Industry And Created The Mobile & Social Web

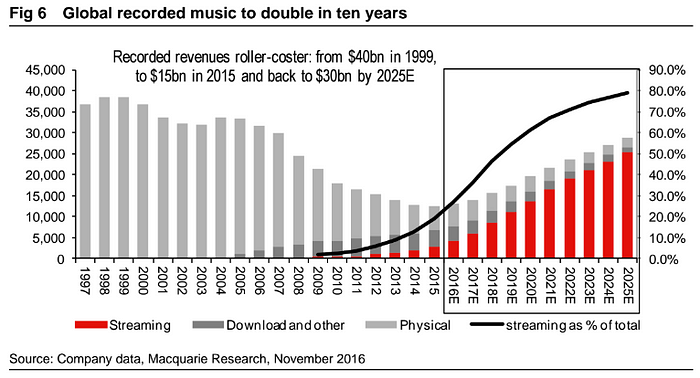

As the music industry recently announced its first annual revenue growth after 15 years of uninterrupted contraction, I thought it was a good time to share some of the things I learnt from reading Stephen Witt’s book How Music Got Free. It provides a fascinating account of how a relatively obscure scientific breakthrough — the discovery by German engineers of “psychoacoustic” principles according to which most of the information in recorded music is in fact inaudible to the human listener and can be thrown away — coupled with the distribution power of the Internet, radically transformed a large and profitable industry in a matter of years. As such, the history of the MP3 gives an excellent framework to anticipate how disruptive 10x innovations impact a market, and who the winners and losers of such breakthroughs will be.

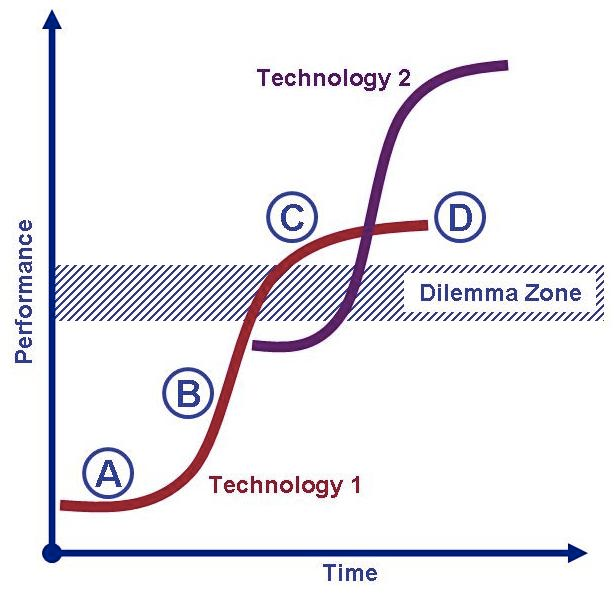

- The MP3 is a perfect case study of Innovator’s Dilemma.

Compared to the CD, the MP3 was an inferior product (lower audio quality) but radically cheaper and more convenient (1/12th smaller data footprint). It initially targeted a tiny niche of users: few people were on the Internet with a fast enough connection at the time, no one had an MP3 player, and there was nowhere convenient to download MP3 files. But following the rapid development of its ecosystem (desktop and then mobile MP3 players, Torrent and then download and streaming services), MP3s rapidly became a better option than CDs for the majority of the population, rendering the previous paradigm obsolete.

“The music industry does not believe in electronic music distribution”

As with other disrupted industries described by Clay Christensen in Innovator’s Dilemma, the incumbent players in the music sector at the time (labels, CD manufacturers and distributors, CD player manufacturers) initially dismissed the innovation as a low quality hack that would never take off. When Karlheinz Brandenburg, the genial inventor of the new format, approached the big record companies to recommend that they adopt a new copy-protected version of the file, he was “informed, diplomatically, that the music industry did not believe in electronic music distribution”. Similarly, when his group showed their prototype of the first portable MP3 player at an engineering fair in 1995, an executive from Philips told them: “There will never be a commercial MP3 player.”

Not only did the incumbents fail to grasp the potential value, but it would have made no sense for them to go after such a small unprofitable niche, which would have been irrelevant to their top line, and eating away at their bottom line (CDs were 90%+ gross margin products back then). By the time they realised what was coming, it was already too late for a lot of them to react — most of the value created would accrue to new entrants.

The dilemma extends beyond misaligned economics incentives. There is also a DNA issue at stake — incumbents simply did not have the right teams to adapt to the changing environment. “There’s no one in the record company that’s a technologist,” Morris explains. “That’s a misconception writers make all the time, that the record industry missed this. They didn’t. They just didn’t know what to do. It’s like if you were suddenly asked to operate on your dog to remove his kidney. What would you do?” Personally, I would hire a vet. But to Morris, even that wasn’t an option. “We didn’t know who to hire,” he says, becoming more agitated. “I wouldn’t be able to recognize a good technology person — anyone with a good bullshit story would have gotten past me.”

2. Engineering Vs. Craftsmanship

In Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance, Robert Pirsig contrasts the narrator’s classical approach to life (and motorcycling) to his artist friend John Sutherland’s romantic stance. While the former owns an older motorcycle which he is usually able to diagnose and repair himself through the use of rational problem-solving skills, the latter simply hopes for the best for his bike and focuses on being “In the moment”, and not on rational analysis.

“Still, this was engineering, where verified results should by necessity triumph over human sentiment.”

A similar dichotomy lies at the heart of the MP3 story, which helps explain the sector’s initial dismissal of the new format as an inferior product. As Witt puts it: “The studio engineers hated the mp3. These were the knob-twiddling soundboard jockeys who actually mixed the albums. Responsibility for the sound quality of recorded albums fell to them, and, in their consensus opinion, the mp3 sounded like shit. […] But it went beyond that — the studio engineers were irredeemable audiophiles who regarded even high-quality mp3s with disdain. For them, capturing the subtle acoustic qualities of recorded music was a professional obligation that bordered on obsession. Now Brandenburg was proposing to irretrievably delete 90 percent of their life’s work. For the studio guys, sound was an aesthetic quality that you described in terms of “tone” and “warmth.” For the researchers, sound was a physical property of the universe that you described in logarithmic units of air displacement.”

We now all know how that battle played out. As Witt concludes: “Still, this was engineering, where verified results should by necessity triumph over human sentiment.”

Watch out for any instances where incumbents bet their future on romantic, non-rational arguments. There is value to be created by betting against them and building better products based on first principles.

3. Network effects win: the revolutionary power of free

While the MP3 was genuinely better than the competing MP2, it was not as good as the AAC, which was designed to be its successor. However, the MP3 won the format war because it was the first “good enough” digital format to reach critical mass. Consumer adoption created a de facto standard that was then impossible to bypass due to network effects.

“Why would anyone purchase a music player if there was no music to be played on it?”

But how exactly, did the German researchers at the Fraunhofer Institute manage to win the market, against better funded and more business-savvy competitors? By doing what countless other consumer social apps have since done: giving real value away for free. After launching the format, they quickly realised that it had no chance to succeed if users did not have a simple way to listen to it. This was the typical chicken and egg problem that any new format faces: it cannot grow unless consumers are equipped to use it, but consumers don’t want to invest in expensive equipment until they know there is enough available content to justify it.

They therefore started by giving away a simple desktop-based MP3 encoder.

“After some internal discussion, Brandenburg made an executive decision: to promote the mp3 standard, Fraunhofer would simply give L3Enc [an encoding software they had developped] away. Thousands of floppy disks were made, and these were distributed at trade shows through late 1994 and early 1995. Brandenburg encouraged his team members to distribute the disks to friends, family, colleagues, and even competitors.

The freeware was quickly appropriated by pirates and turned it into a weapon of mass MP3isation.

“Using Fraunhofer’s L3Enc encoder, NetFraCk had started a new crew, the world’s first ever digital music piracy group: Compress ’Da Audio, or CDA for short. On August 10, 1996, CDA had released to IRC the world’s first “officially” pirated mp3: “Until It Sleeps,” by Metallica, off their album Load. Within weeks, there were numerous rival crews and thousands of pirated songs.”

The German researchers then proceeded to develop the second critical component in digital music consumption: the desktop MP3 player, which, this time, they decided to distribute as a freemium product.

“Grill finished the program in July and began distributing it on floppy disk as “crippleware.” WinPlay3 had the capacity to play twenty songs, and then, like a message from the Impossible Missions Force, it self-destructed. If you wanted to continue using it past that point, you were required to send a registration fee to Fraunhofer and wait for them to send you back a serial number.”

Hackers quickly cracked the arbitrary twenty songs limit, heralding the era of free, unlimited, digital music.

“The Fraunhofer team were no strangers to the Internet, but the Internet they knew was a collaborative tool for research and commerce, not some grimy subculture of anonymous teenage hackers. In their naiveté, they had not seen what was coming. Somewhere in the underworld, L3Enc, the DOS-based shareware encoder Grill had programmed several years back, was being used to create thousands upon thousands of pirated files. Meanwhile, somewhere else in the underworld, the commercial WinPlay3 player that supposedly self-destructed after twenty uses had been cracked, enabling full functionality. Together, the two were now being distributed in chat rooms and websites as a bundled package.”

While it may not have taken the shape they had originally envisioned, Brandenburg and Grill’s freemium distribution strategy is what created the MP3’s network effect it needed to dominate the market, even against more technologically sophisticated formats.

4. From the MP3 to the P2P revolution

But no matter how efficient the format and how convenient the player, no user would have been interested in taking part in the MP3 ecosystem without an easy way to access all this exciting new content. A new distribution infrastructure had to be built, superseding the brick-and-mortar record stores.

“With torrents, the more people who attempted to simultaneously download a file, the faster the download went.”

But sharing large catalog of heavy digital files on a global scale presented unique technical challenges, which the invention of torrents and their underlying P2P technology brilliantly solved.

“The greatest benefit of the torrent approach was the way it solved one of the Internet’s long-outstanding problems: the traffic bottleneck. Historically, popular files tended to crash servers, as millions of users crowded around a narrow doorway and tried to push their way in. But the matching schematic of torrents opened hundreds of doors at once, taking pressure off the server and transferring it to individuals. This inversion of the traditional paradigm of file distribution had a startling result: with torrents, the more people who attempted to simultaneously download a file, the faster the download went.”

Launched in 1999 as the more commercially mature incarnation of P2P tech, Napster demonstrated how quickly the technology could scale, both from an infrastructure and consumer demand point of view.

“Napster was a natural monopoly whose selection and speed only improved as more people joined. By early 2000 there were almost twenty million users, and by summer over 14,000 songs were being downloaded every minute. Every song ever produced anywhere could be procured in seconds. Download speeds were improving rapidly, even from a home connection, and songs often arrived in less time than they took to listen to. In essence, the song could be streamed. Napster wasn’t just a file-sharing service; it was the infinite digital jukebox. And it was free.”

Despite its eventual shutdown, Napster and other successful file sharing sites laid the technical and business foundations that the social web built on later on. It is no coincidence that early participants in these ventures ended up in the founding teams of companies like Facebook and Skype.

5. The emergence of a new value chain

The MP3 didn’t only change the way music got distributed, but transformed its entire value chain, from production and manufacturing to the role of the labels, and even the job of an artist. As with every other industry touched by the Internet, by dramatically lowering barriers to entry, the new format made it possible to bypass various middlemen and gatekeepers.

“Morris had once been a gatekeeper, the guy you needed to get past to get into the professional music studio, and the pressing plant, and the distribution network. But you didn’t need any of that stuff anymore. The studio was Pro Tools, the pressing plant was an mp3 encoder, and the distribution network was a torrent tracker. The entire industry could be run off a laptop.”

Labels have not disappeared though, but their revenue model has had to change, moving away from album sales towards all-encompassing “360” deals.

“Even as they abandoned the album, fans started arriving in droves to large-scale integrated music festivals. […] from 1999 to 2009 concert ticket sales in North America more than tripled. At the same time, increased demand from advertisers and sample-driven music producers led to a period of spectacular growth in the music publishing business. […] In response to these shifts, music executives began pushing artists to sign “360” deals that guaranteed labels not just a portion of album sales but live music and publishing rights as well. While 360 deals were controversial, artists still seemed to need labels, even in the digital era, and many, sometimes against their better judgment, signed on.”

6. Second and third order consequences: value goes up for complements and down for substitutes

A recent article in the Harvard Business Review titled “The Simple Economics of Machine Intelligence” offers a useful framework to think about the systemic impact of disruptive innovation. It goes as follows: “When the cost of a foundational input plummets, it often affects the value of other inputs. The value goes up for complements and down for substitutes. In the case of photography, the value of the hardware and software components associated with digital cameras went up as the cost of arithmetic dropped because demand increased — we wanted more of them. These components were complements to arithmetic; they were used together. In contrast, the value of film-related chemicals fell — we wanted less of them.”

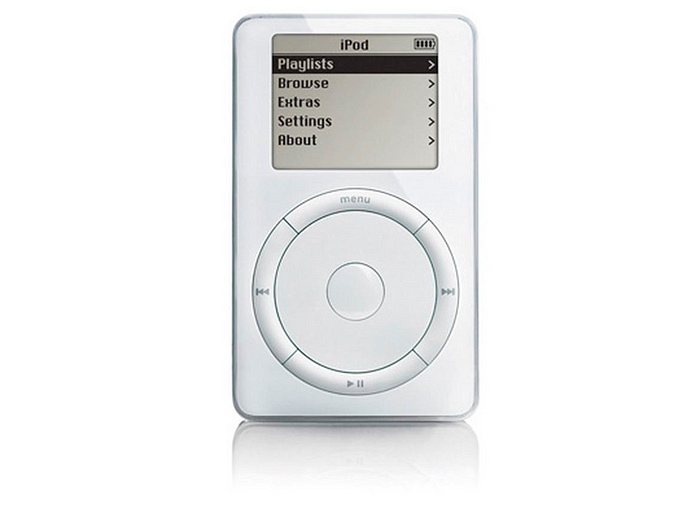

In the case of the MP3, while it rendered the CD (a substitute) and its value chain obsolete, it created large complementary winners in distribution (Spotify), connected speakers/headsets (Sonos, Beats), or live music. But the most successful complementary technology of all has unquestionably been the portable MP3 player, the iPod in particular. It kickstarted Apple’s renaissance and served as the launching pad for the iPhone and the smartphone industry as a whole.

Whether it’s artificial intelligence, self-driving, blockchain, 3D-printing, or any other new disruptive technology, it’s useful to think in terms of complements and substitutes to identify winners and losers, and more accurately predict second and third order consequences, beyond the immediate impact on a narrow market.

7. Are VCs music labels in disguise?

As Witt was describing the day to day job of Doug Morris, once the most powerful executive in the history of music as head of Warner, I couldn’t help but notice how similar it was from mine as a VC. Find ways to identify talent earlier than competition, fight to sign exclusive agreements with them, spot the future winners and invest massively on them, as most returns are generated by a few outliers. Sounds familiar?

Morris even rose through the ranks by leveraging another one of VCs’ favourite tools: data.

“The shift in roles required Morris to pay closer attention to sales, but in the 1960s keeping score was difficult. Record stores weren’t always inclined to share their sales figures, and even if they had been, in an era before computers, collecting and sorting the data from thousands of retailers around the country was impossible. Only one person at Laurie could provide the numbers Morris needed, a functionary clerk whose real-world job was about as far away from the glamour of the music business as you could get: the order-taker. Morris haunted him like a ghost. Whenever a big order came in Morris demanded to know who had placed it, exactly how many units they wanted, and why. The order-taker was understandably perplexed. Shouldn’t Morris be at a nightclub somewhere, looking for the next Jimi Hendrix, instead of here, in the accounting department, pestering a back-office employee? But to Morris the order-taker was the key to the whole thing. How could he know what to sell if he didn’t know what people were buying? […]

Morris never forgot the experience of his first gold record, and he began to trust market research more than he trusted expert opinion — more, sometimes, than he trusted his own ears. Let the other A&Rs scout bands, and go to nightclubs, and fall in love with demos. Let them guess at trends, and fool themselves into believing they had some special insight into the next big thing. From now on, Morris was scouting the order-taker.”

The evolution of music labels can therefore provide a relevant blueprint for the VC industry. In the same way that the switch to digital rendered the labels’ analogue monopolies obsolete, and made it possible for artists to bypass them and go direct to their audience, new tools like crowdfunding, online marketplace or even Initial Coin Offerings can challenge the traditional VC model, built around privileged LP access and proprietary dealflow. Some new VCs have attacked the market by offering more services to entrepreneurs (eg. A16Z). Others by sourcing talent earlier and at scale with a standardised low price high volume model (eg. YC). All forcing established players to keep improving on their offering.

The analogy is not perfect: VCs never enjoyed the market power and subsequent rent that music labels did, which has forced us to remain small and nimble. Online has so far been complementary rather than substitutive. But it is an interesting analogy nonetheless, as the key question remains the same: how can intermediaries keep providing value in a fully digital economy where platforms can match supply and demand with greater efficiency and scale? Tomorrow’s winning VCs will be the one who find the right answers to this question.

Conclusion

As a conclusion, I’d highly recommend reading Stephen Witt’s book. His account of the dark underworld that powered the early days of the digital music ecosystem is fascinating, as is his in-depth description of characters as extraordinary as Brandenburg and Morris. But even more interesting is the step by step breakdown of the impact a single algorithm has had on both the music and the tech industry at large. It provides another excellent case study of innovator’s dilemma, and a great framework to predict the future impact of nascent disruptive innovations. Whether it’s autonomous vehicles, 3D printing, bitcoin or AI, many radical innovations have recently appeared which have the potential to upend existing industry value chains by offering 10x improvement in cost and convenience. And as with the MP3, some of them may unleash second, or even third order consequences, as significant as Apple’s rise to dominance.