“One summer day, probably in the 1870s, friends of a major short-seller got together on the shores of Newport, Rhode Island, where they admired the enormous yachts of New York’s richest brokers. After gazing long and thoughtfully at the beautiful boats, the short seller asked wryly, ‘Where are the customers’ yachts?’”

Jason Zweig, in his introduction to Fred Schwed’s 1940s Wall Street classic, “Where Are the Customers’ Yachts – A Good Hard Look at Wall Street”

If investors complained about Wall Street 80 years ago, they’re howling now. Industry players get richer and richer, while many investors see mediocre results after fees.

Asset management is a highly unusual and somewhat baffling industry. We see six main examples of just how peculiar our industry is, relative to other industries:

1. The asset management industry rarely delivers what it promises, alpha. “Alpha is a zero-sum game”, according to Bridgewater founder Ray Dalio. By contrast, most industries are positive-sum: if you eat a great steak dinner, it doesn’t imply that others have to eat hot dogs. In asset management, each new Money Manager that is able to generate Alpha (returns above the passive benchmark performance) normally does so at the expense of other Money Managers who underperform. Your own investment’s value may change because of a change in the value of the underlying asset and/or market preferences. However, few investors can directly impact the value of the underlying asset, except for private equity and venture capital investors with portfolio acceleration strategies. Celebrity investors like George Soros can influence market preferences, but most of us don’t have that advantage. In fact, it is mathematically impossible for the mean active investor in a given sector to beat a low-cost index of that sector after expenses.

We’d argue that money managers playing a positive-sum game include those who focus on sectors for which indices are not readily available (e.g., private companies, frontier markets, cryptocurrencies) and/or nascent asset classes. In addition, if an investor impacts the operations of a company, they are playing a positive-sum game. For example, activist hedge funds, and most private equity and VC funds. When a hedge fund investor makes a trade, they can then only pray, hedge, or sell. A private equity/VC investor can proactively recruit new team members, win clients, or if necessary change management.

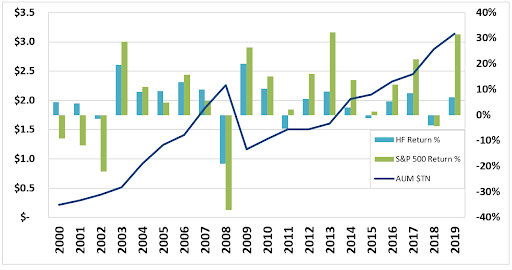

Hedge funds on average have underperformed on a net of fees basis in both US equities and bonds since 2000. The HFRI Index returned 18.3% annually during its inaugural ten years from 1990 to 1999, but it returned just 3.4% annually over the last twenty years. Even sophisticated investors like Warren Buffett ask questions about the value of active investing.

Rolling ten-year returns have steadily declined across hedge fund strategies

Sources: Blue Bar: Hedge-Fund Research Institute Weighted Composite Index (HFRI FWD)

Sources: Blue Bar: Hedge-Fund Research Institute Weighted Composite Index (HFRI FWD)

Green Bar: Bloomberg

Blue Line: Barclays Hedge-Fund Industry; 2017

Nicolas Rabener, Managing Director, Factor Research, observes, “Given better analytics, institutional investors have realized that there is little alpha and much of the excess returns are explained by risk premia.” Worsening the situation, Amit Matta, a risk management expert, observes that performance is often overstated (and risk understated) due to the illiquid nature of some of the underlying investments, which allows room to manipulate pricing in favorable ways.

Dimitri Sogoloff, CEO, Horton Point, observes that the market would be truly zero-sum if ALL of the participants were asset managers. However, a large group has different objectives – corporate players. “They are fully 50% of the primary market (sellers) and are material players in the secondary market (M&A), which cumulatively makes the markets a positive-sum game. It’s possible for all asset managers to make money when they buy a successful IPO or sell their holding to a corporate buyer.”

2. Standard compensation models motivate Money Managers to add more assets under management, but size often hurts returns. This contributes to the ‘winner takes all’ trend in which we see a steadily growing concentration of AUM into the largest money managers.

Among hedge funds, the argument is that large funds have the resources and talent to beat markets. The reality has been far from that. After years of lackluster returns, during the 2020 market crash due to the coronavirus pandemic, even a number of the most prominent hedge funds unexpectedly lost money exactly when they should have been providing diversification and downside protection.

Alternative investment funds earn on average two-thirds of their compensation from management fees, not carry or performance fees. Large hedge funds over time hit liquidity limits and start impacting market pricing when they trade, losing their ability to exploit arbitrage opportunities. For example, one of the challenges for the widely popular Risk Parity strategy going forward has become size and liquidity. Risk Parity strategies peaked at $1 trillion at the end of 2020, but a combination of losses and redemptions shrunk its collective AUM to $400m in less than a quarter. Risk Parity has failed to deliver on its ambitious promise to be an all-weather strategy. Just when investors most needed its diversifying capabilities in Q1 2020, risk parity strategies underdelivered in comparison to a low-cost, boring 60%/40% bond equity mix.

Similarly, large VCs earn lower returns than small VCs, who in turn earn lower returns than angel investors; angels writing small checks have among the highest returns of any asset class. Of course, it is true that large size does create certain proprietary advantages, e.g., some large fund of funds negotiate preferential management fees from funds in which they invest. Large hedge funds also have the resources to invest in data, technology, and talent, helping them to remain consistently competitive.

3. The “broken agency” principal-agent conflict can cost money holders far more than the same problem does in most other industries. All companies face some form of the principal-agent problem, e.g., the CEO of a public company may be tempted to manage financial results to optimize the short term stock price if a significant portion of her compensation comes from company stock options. In asset management, the principal-agent problem is exacerbated by the presence of so many conflicted intermediaries. For example, an individual allocator is often motivated to allocate to the most popular fund or type of investment in which her peers are investing, to protect from career risk. If an allocator hires a known player, underperformance will not cause the employee’s judgment to be questioned. The resulting herd mentality hurts innovation and leads to suboptimal returns.

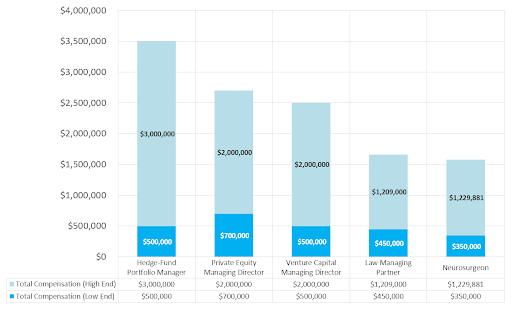

4. Money managers can earn more money at less personal risk than in most other industries. Simon Lack reports in The Hedge Fund Mirage that from 1998 to 2010, hedge fund managers earned $379 billion in fees, while their investors earned only $70 billion in investment gains net of fees. In the asset management industry, the norm is that the General Partner puts in just 1-2% of the total assets under management and keeps the remainder of her personal assets in a diversified portfolio. Some hedge fund managers have even set up their own sophisticated family offices specifically to diversify their holdings out of the core product in which they made their wealth. In contrast, entrepreneurs in most other fields risk a more significant portion of their own capital in their new venture, better aligning incentives.

Money managers can earn more money at less personal risk than in any other industry

Column 1. Mergers & Inquisitions; Brian DeChasare; “The Hedge Fund Career Path: The Complete Guide”

Column 2. Mergers & Inquisitions; Brian DeChasare; “The Private Equity Career Path: The Complete Guide”

Column 3. Mergers & Inquisitions; Brian DeChasare; “Venture Capital Careers: The Complete Guide”

Column 4. Yale & “Major, Lindsey, & Africa”, Jeffrey A. Lowe; “2016 Partner Compensation Survey”; 2016

Column 5. MGMA, “The 2019 MGMA Physician Compensation and Production Report”, 2019

We are obliged to note that this particular misalignment is less of an issue in early-stage VC, where small fund size and illiquidity means that even with great performance, most investors will at best “get rich slow”.

5. The financial services industry, including asset management, has disproportionate power to create systemic economic risk, which in turn can create a risk of social instability. This negative externality is unique to financial services and was particularly obvious in the 2008 Global Financial Crisis. Similarly, when the highly leveraged Long Term Capital Management fund collapsed in the late 1990s, sixteen leading financial institutions had to agree on a $3.6 billion recapitalization (bailout) under the supervision of the Federal Reserve. By comparison, when oil prices doubled between 2009 and 2011, it created stress for some industries, but there was no concern that the global economy would collapse. The picture was no different in early 2020, when markets experienced the COVID-19 shock. To avoid a market melt-down, governments and central banks around the world jumped in a concerted effort to create liquidity, thus providing the biggest bailout in history for investment managers. The scope of the liquidity infusion has been massive even by the 2008 standard. Post the 2008 financial crisis, when interest rates reached close to 0% and the Fed was running out of ammunition, the Fed started buying treasuries at $85 billion a month. In 2020, the Fed was far more aggressive; in a week the Fed injected the same liquidity that it had injected during the entire post 2008 recovery:

The majority of new debt is being added to governments as they step in to become the lender of last resort for everyone from large investment managers to corporations, small businesses, and individuals. The macroeconomic backdrop creates the biggest challenge for investment managers: How to create value given the increased involvement of the Fed in markets, as fiat currencies get effectively debased.

6. The investment management industry is far more homogeneous than the clients it serves, ironically for an industry that worships “diversification” as the one true free lunch. There has been virtually no progress in adding women and minorities as asset managers. According to Pension & Investments , only 1.4% of asset under management are managed by women or minorities. This, despite the fact that funds run by women outperform. That outperformance equals the cost of money holder bias. Distributors (e.g., Registered Investment Advisors) also are disproportionately white men of middle age and older. The bias has two other main negative effects. First, it limits investors’ understanding of the world. Americans with two white parents are expected to be less than half the US population by approximately 2045. Inevitably consumption and behavior patterns will evolve accordingly. Second, observes Carol Morley, CEO of the Imprint Group: “It is hard to attract top talent if firms are looking at a small slice of the population and their immediate peer group.”

Asset Management Headcount by Gender and Ethnicity

In reviewing this list of 6 ways in which our industry is unusual, we think that the industry will most quickly normalize in incorporating more diverse decision-makers. Diversity & inclusion are the most readily solveable issues of those we list above, and the inevitable aging of the “pale, male & stale” leaders of the industry will create room for new entrants.

Continue reading…

This is part of a series on disruption of investment management that I co-wrote with Katina Stefanova, CIO and CEO of Marto Capital, a multi-strategy asset manager, which creates customizable investment solutions for institutional clients. We based this on interviews with over 50 family offices, sovereign wealth funds, endowments, pensions, and other institutional investors.

- The Peculiar Investment Management Industry

- The Macro Trends Forcing Change on the Investment Management Industry

- What are the “Jobs To Be Done” of an Investment Manager?

- The Investment Manager of the Future

We wrote the first version of this research with Brent Beardsley, formerly a Partner with Boston Consulting Group.

Contributors

This study would not have been possible without the collaboration and support of Brent Beardsley and the Boston Consulting Group. We also want to thank the research, technology, and editorial team who supported us during this study: Greg Durst, Jen McPhillips, Jenny Wong, Charles McLaughlin, Michael Rose, and James Ebert, plus more recently Ariel Cohen, Caleb Nuttle, Spencer Haik, and Cormac Ryan of Bullet Point Network, where David Teten is an Advisor.

I published in 2013 a much earlier version of this in Forbes, and in December 2020 published the final version in Techcrunch.

Photo credit: JD Hancock.

Sources: Blue Bar: Hedge-Fund Research Institute Weighted Composite Index (HFRI FWD)

Sources: Blue Bar: Hedge-Fund Research Institute Weighted Composite Index (HFRI FWD)