The Exchange is back after its brief hiatus. Anna and I have some really neat stuff planned, so stick with us every morning this week. — Alex

Building a consumer-facing fintech company is expensive. And if you want to build one in a sector crowded by both incumbent companies and richly funded startups, it can be super expensive.

That was the lesson we learned in late 2020 by examining operating results from a number of neobanks.

Neobanks are essentially software layers atop banking infrastructure, offering consumers digital-first, mobile-friendly and often lower-fee banking services. The push to rethink consumer banking is a global effort, with neobanks cropping up in essentially every market you can think of. Private investors have shown up in droves to fund competing neobanks because they have the potential to secure users — customers — that generate revenues for long periods of time.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money. Read it every morning on Extra Crunch or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

Investors have proven more than willing to fund huge investments in growth and product at many neobanks, leading to steeply negative operating results at the unicorns. In short, while American consumer fintech Chime has disclosed positive EBITDA — an adjusted profitability metric — many neobanks that we’ve seen numbers from have demonstrated a stark inability to paint a path to profitability.

Recent results from Revolut that TechCrunch covered earlier this morning show that the company had a deeply unprofitable 2020. But if we dig into its quarterly results, there’s good news to be found. Neobanks could be maturing into their cost structure at last.

So today we’ll parse the key Revolut financial results and look at what we can dig up from Starling and Monzo. Perhaps the somewhat good financial news from Revolut is not merely to be found at just one neobank?

Revolut’s 2020

Our own Romain Dillet has a broad look at Revolut’s business here, if you would like a wider lens. We only care about its raw financial results at the moment.

Here are the big numbers:

- 57% revenue growth from £166 million in 2019 to £261 million in 2020.

- Gross profit growth of £123 million in 2020, up 215% from 2019.

- Gross margin of 49% in 2020, what Revolut described as nearly a doubling.

- 2020 operating loss of £122 million from £98 million in 2019.

- Total loss of £168 million in 2020, up from £107 million in 2019.

The gist of these figures is that the company’s revenue growth was solid, but improving gross margins allowed its gross profit to spike in 2020.

If the company’s gross profit shot higher, however, how did Revolut manage to lose so much money at the same time? Well, the company had a massively uneven year from a profit perspective.

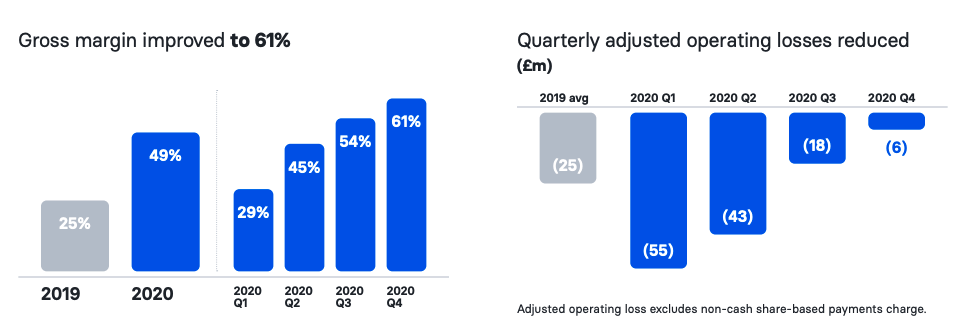

Check out the following charts from its own report:

Image Credits: Revolut

We can see the obvious connection between gross margin — the percentage of revenue that is left after it pays for itself — and the company’s operating losses. Indeed, as the company’s gross margin grew to 61% in Q4 2020, Revolut’s operating loss fell to just £6 million.

And the good news continued in Q1 2021. Here’s the company’s CFO from earlier today:

Revenue increased by more than 130% vs Q1 2020. … Gross profit grew by more than 300% vs. Q1 2020, with meaningful gross margin expansion driven by our product mix and continued ownership mentality on cost control. Adjusted operating and net income margins were above 30%. We have continued to grow our retail customer base and finished the quarter serving 15.5 million personal customers.

Hot dang. That’s a fiery start to the year. Revolut, then, did lose a lot of money in 2020, but those losses were heavily weighted toward the front of the year, at least in operating terms. Things got better as the year rolled along, and 2021 is looking good for the company.

Revolut is not alone in posting encouraging neobanking results. When Starling Bank raised £272 million earlier this year, it announced a number of its own results. Here are the core figures:

- £12 million January 2021 revenue, up 400% from January 2020.

- “[B]roadly flat” gross operating costs.

- The company “generated a positive operating profit for a fourth consecutive month” in January, “with net income now exceeding £1.5 million per month.”

Customer accounts also nearly doubled on a year-over-year basis, the company said. That’s all pretty damn positive. Toss in what we know about Chime’s ability to generate adjusted profits and we have a trio of neobanks in the market today that appear set to not only survive, but possibly thrive, in the long term.

Not all the 2020 neobanking news is good, however. Monzo last raised a down round as 2020 closed out, and its most recent results — rather dated now, it must be said — were stark in their unprofitability.

Even if we presume that Monzo has not improved its own profitability metrics since we last got our hands on them, the financial picture that Starling, Revolut and Chime paint as a group is encouraging. For investors who have poured billions into the neobanking boom, that’s good news. Ditto for the employees of those companies and your parents’ pension fund, which likely has exposure to the venture asset class, and thus perhaps some of the companies we’ve discussed today.

Neobanking has yet to show that it can generate positive, growing free cash flows over a multiyear period. But their results at least indicate that such incomes could occur in time.