Scooter unicorn Bird is going public, per an agreement to merge with a special purpose acquisition company, or SPAC. After rumors and reports circulated for months about an imminent deal, it has finally arrived.

First, a quick overview of the agreement and the players involved: Bird is merging with Switchback II at an implied valuation of $2.3 billion. Fidelity Management & Research Company will lead the deal’s $160 million in private investment in public equity, or PIPE. Apollo Investment Corp. and MidCap Financial Trust provided an additional $40 million in asset financing. (Disclosure: Apollo is buying TechCrunch’s parent company.)

Historically — and based on what we’re seeing in this fantastical filing — Bird proved to be a simply awful business. Its results from 2019 and 2020 describe a company with a huge cost structure and unprofitable revenue, per filings. After posting negative gross profit in both of the most recent full-year periods, Bird’s initial model appears to have been defeated by the market.

What drove the company’s hugely unprofitable revenues and resulting net losses? Unit economics that were nearly comically destructive.

Some of the numbers Bird shared in its investor deck show a business that is growing, in terms of users and geographic footprint. Bird is in 200 cities globally and reports more than 95 million rides to date, and 3 million new riders added during the pandemic. The investor deck also touts year-round positive economics during the COVID-19 era. That all looks positive. But looking into the line-item financials, a different story emerges.

The scooter shop managed to convert a $135.7 million gross loss in 2019 to a smaller gross deficit of $23.5 million in 2020, but it did not manage to shake up its upside-down economics during its full fiscal 2020.

Update: Bird provided a response to questions about its newer fleet management business and how it expects to stem losses. Their response:

Bird’s history to date has been one of milestones. First was securing product market fit and delivering an eco-friendly way for people to travel in their communities and access opportunities – education, health and economic. The second milestone focused on unit economics and laying the foundation for a sustainable business. Then came the pandemic, which served as a catalyst for us to identify how to scale in a way that allowed us to be profitable at a ride level. As a result, in H2 2020 our ride profit (after vehicle depreciation) was positive and people are continuing to embrace naturally social distanced eco-friendly options.

The startup lost $387.5 million in 2019 and $208.2 million in 2020 while shrinking. Also, note that Bird was able to reduce some costs by laying off 400 people in 2020.

Bird generated $79.9 million in revenue from shared rides in 2020, a 43% drop from the previous year. Meanwhile, on the product sales side, Bird saw revenue grow 30% year over year to $14.66 million. In all, the company brought in $94.6 million in 2020 — a nearly 37% reduction in revenue from 2019. Of course, COVID-19 is largely to blame, but that still doesn’t diminish the losses.

What drove the company’s hugely unprofitable revenues and resulting net losses? Unit economics that were nearly comically destructive. Per the company’s investor presentation, its fiscal 2018 saw -348% ride profit as a percentage of so-called “sharing” revenue inclusive of depreciation. Those numbers did improve throughout its fiscal 2019, and into last year.

Inside of its fiscal 2020, however, there’s some nuance worth bringing up. Bird’s “ride profit” economics did improve into positive territory in the second half of the year. How did it drive that change? By shaking up its entire business model.

OK, what’s their new plan?

Bird’s initial model of buying its own scooter fleets and deploying them around the world has failed. Financial results demonstrate that fact, as does the company’s business-model shift to empowering others to build scooter fleets under its brand name. Or more simply, Bird went “franchise” during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Per its SPAC deck, fleet-manager-derived revenues during the second half of 2020 made up 94% of its “sharing” revenue. Allowing fleet managers to run Bird scooters in their cities has also seemingly unlocked smaller markets, and it claims these new regions have better economics than large cities.

Bird was famous in its early life for competing with Lime in head-to-head competition in large markets. That was a costly error, it appears. Per Bird, its “ride profit margin” after taking into account “vehicle depreciation” is just 10% in large cities, but 19% in smaller markets. Bird did just land a permit in New York City. (Update: But lost access to its home market in Santa Monica.)

Adding the company’s more efficient — read: less economically catastrophic — model of partner-fleet spec deployment of its hardware to smaller markets, and Bird thinks it has a shake at both growth and an end to the torrent of red ink that it has posted thus far in its life.

On the growth front, do we embrace the company’s projections? No, but a somewhat compelling recent growth curve should entice investors. From its deck:

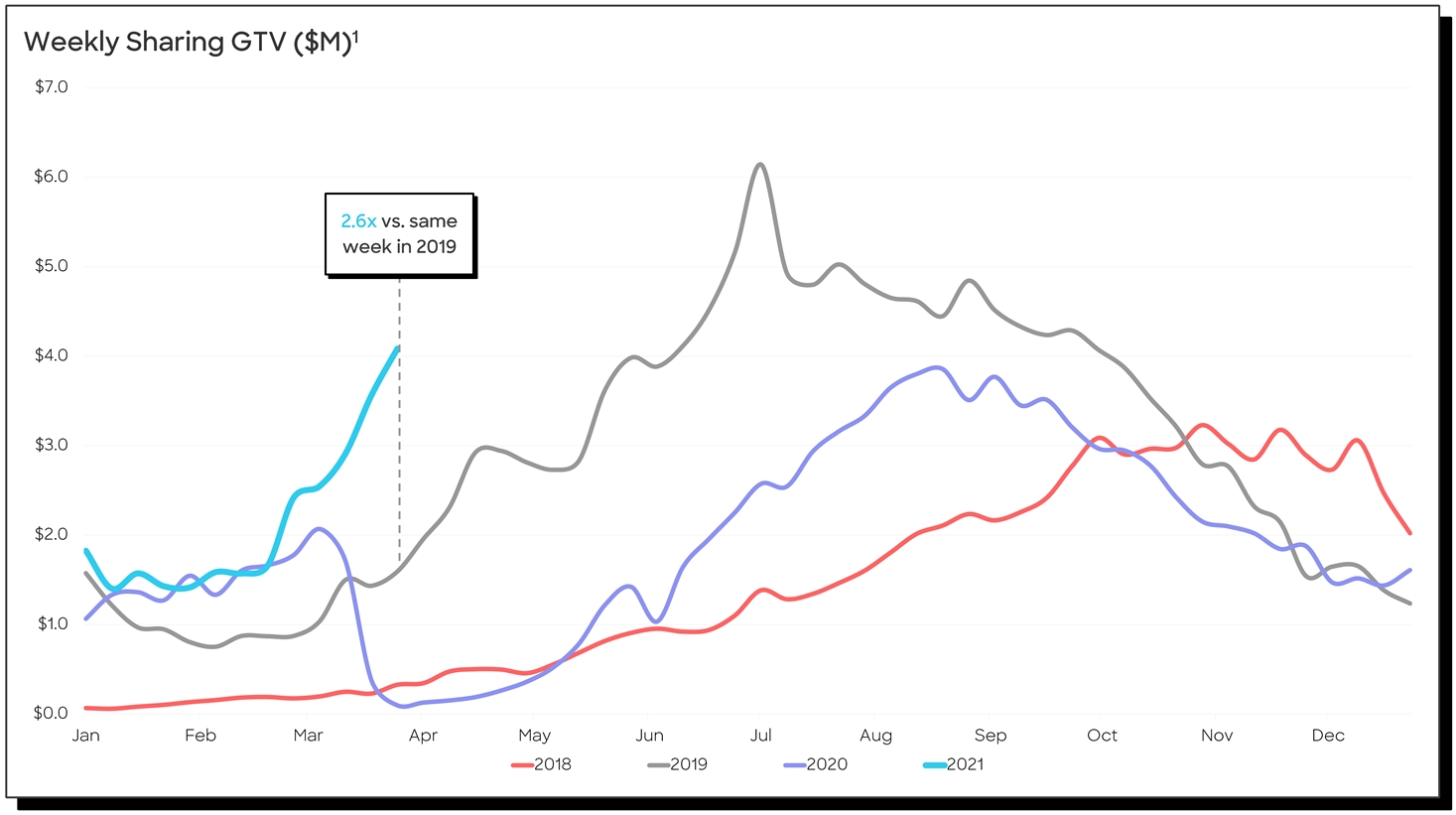

The company will have, if nothing else, some very strong year-over-year results to display during 2021 because it will be contrasting its own performance against what COVID-19 did to its results last year. But because Bird is also outpacing its 2019 sharing GTV, it is, in fact, growing against a more regular period.

So stronger economics and some growth? What’s not to like? Many things. Despite improving scooter-nomics in the second half of 2020 as noted above, Bird still posted a negative gross profit in Q4. Sure, it did manage to squeak $600,000 in gross profit during Q3 2020, but that’s effectively a single period of break-even results after years of investment and work.

Investors betting on Bird had best get accustomed to sharply negative GAAP numbers stacked next to improvements in heavily adjusted metrics. In the period in which Bird finally managed gross-profit positivity, it also posted an adjusted EBITDA loss worth 65% of its revenues. And then the company shrank in Q4 2020 thanks to the cyclical nature of its business.

Other delights

The filing revealed details on a few other mysteries around the company’s operations.

Take its acquisition of Scoot in 2019. Bird didn’t disclose the purchase price at the time. Now, we know that Bird paid $8.6 million for Scoot. The acquisition was paid for through half a million dollars in cash and the issuance of an $8.3 million convertible note with a $200,000 debt discount. Bird then converted the convertible notes from the acquisition into 640,261 shares of Series D-1 redeemable convertible preferred stock.

It is not clear if the Scoot deal provided a material benefit to Bird’s operating results.

Then there is Circ, the Berlin-based micromobility startup it acquired in January 2020. Bird acquired Circ for $190 million of Series D and Series D-2 redeemable convertible preferred stock. Through the deal, Bird acquired $68.7 million of cash and $5.5 million in so-called intangible assets.

In June 2020, Bird shut down scooter-sharing in several cities in the Middle East, an operation that was managed by Circ. At the time, Bird couched the shutdown as “pausing of operations.” Bird’s decision to shut down, or pause, Circ’s entire Middle East business affects operations in Bahrain, UAE and Qatar.

We’ve reached out to Bird for comment and will update this story when they respond.

Update: A few percentages in the revenue section have been corrected. We initially did the math wrong.